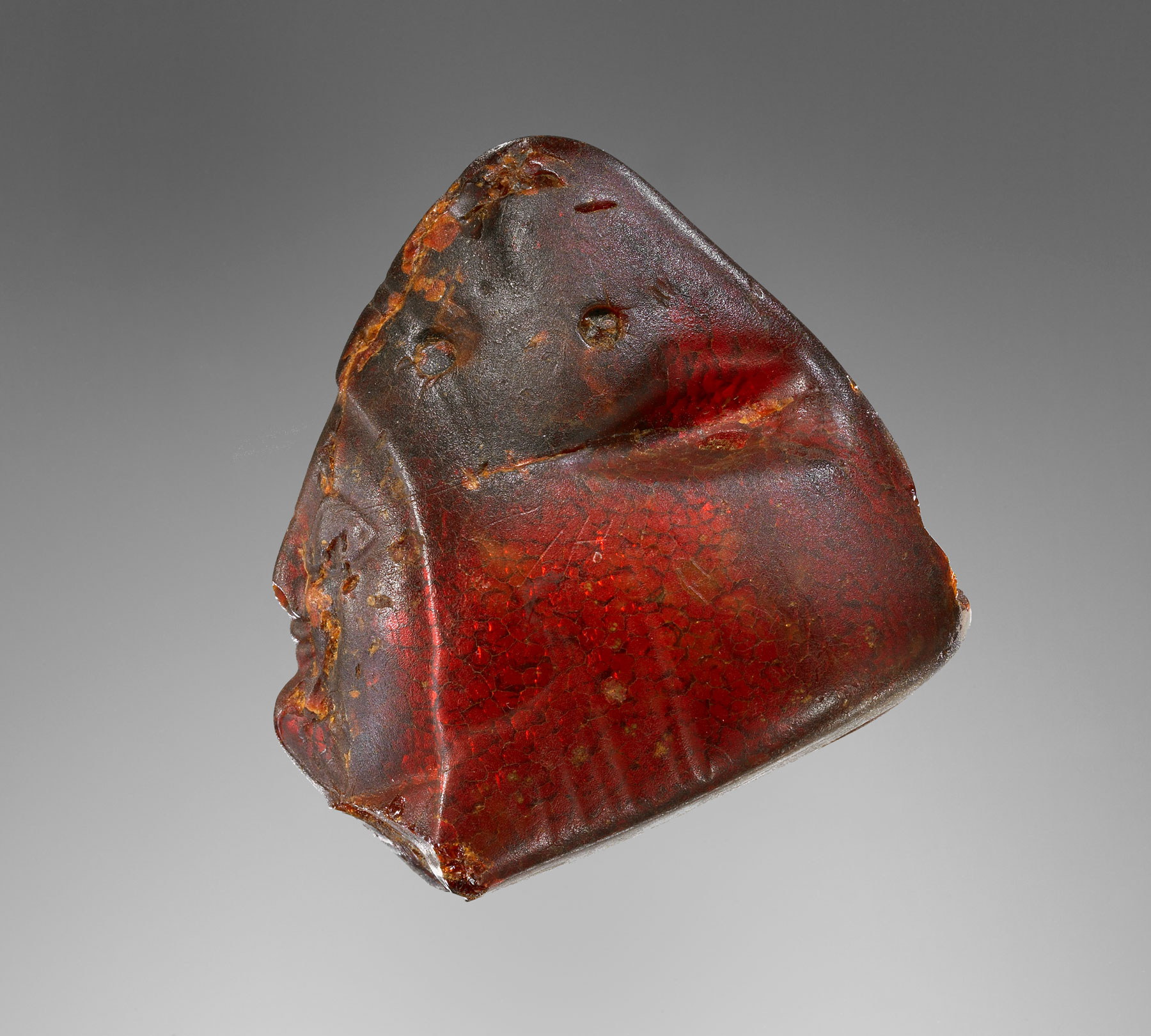

15. Pendant: Winged Female Head in Profile

| Accession Number | 76.AO.85.2 |

| Culture | Etruscan |

| Date | 525–480 B.C. |

| Dimensions | Height: 79 mm; width: 49 mm; depth: 25 mm; Weight: 51.3 g |

| Subjects | Inclusions |

Provenance

–1976, Gordon McLendon (Dallas, TX), donated to the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1976.

Condition

A piece broken off at the neck in modern times was reattached with an adhesive before the donor acquired it. There is evidence of ancient use wear on the prominent parts (cheeks, nose, head, chin, and wing) and abrasion troughs on the uppermost parts of the suspension perforations at the top of the head. (The weight of the pendant, gravity, movement, pulling, or other abrasive action caused the carrier to deepen, or “saw,” the holes.) Modern damage includes pitting on the neck and cheek and large fracture losses at the right profile edge, at the forehead, and in the front section of the hair. The surface of the amber is firm and stable although abraded slightly and crazed overall. Several large fissures (with inclusions and degraded material inside) run throughout the piece, and there are other small areas of inclusions throughout the pendant. In ambient light, the surface of the amber is dark red-brown and opaque; in transmitted light, the pendant is dark red and translucent.

Description

The pendant depicts the head and neck of a female figure in profile facing to the right. It is rounded and decorated on the obverse, flat and plain on the reverse. The area around the eye is subtly modeled. Brow ridge, eye fold, and eye bag are all indicated. The spherical shape of the eye is suggested and set off from lids that are represented as raised lines. The cheeks are full, raised, and puffed; the face is smiling widely. The chin is full and rounded, and the jawline is set off from the neck by a groove as well as modeling. The neck is plump.

The hair is visible at the brow and at the right side. At least five overlapping scalloped waves once framed the face; the remaining ones lie close to the head and are defined with finely engraved parallel curving lines. Horizontal indentations behind the ear area and a curved line at the bottom indicate the shape of the hair fall. The shape and bulk of the head covering shows that over a cap (the conical projection at the back of the head is its apex) is worn a veil and, over it, a shawl. The outermost layer of the headdress is banded with a pattern of finely engraved parallel lines, perhaps a decorative woven edge, or an addition.

A striking feature of this piece is a large volutelike wing, projecting from the right top side of the head and curving back to the neck. Diagonal engraved lines at the top and back indicate secondary feathers. In front of and below the wing are sections of hair, engraved with horizontal parallel lines; the mass of the hair is curved at the bottom.

The smoothed grooves and craters are likely the result of the clearing away of surface inclusions or fissures in the amber blank. The object incorporates the natural undulations of the amber, especially at the back and in the wing area.

The pendant has two through-bores for suspension. The first is a lateral perforation at the crown 2.5 mm in diameter, with a hole in the front of the head, at the border of the head covering, and another in the top of the head. At the position of the ear is the second through-bore, 9 mm in diameter, which appears to have been made after the head-pendant was carved. There are also five stopped bores; the longest, 22 mm in length by 4 mm in diameter, begins under the chin, ascends vertically to the hairline, runs parallel to a long internal fissure, and does not retain a plug. Two other stopped bores, one of which retains its plug, are located on the forehead. The two others, at the back of the head and on the reverse, are without plugs. It is not possible to determine how this pendant would have hung, because of the multiple through-bores.

Discussion

One of the largest of the extant amber head-pendants, 76.AO.85.2 has no close counterpart. It is also significant within the corpus of head-pendants because of its style, iconography, evidence of use wear, and quality.

The figure wears several elements of dress that cover her head: a cap, veil, and shawl or mantle. In this, the combination is comparable to the dress worn by (cat. no. 14). For the dress, the best parallel is an Etruscan bronze in Florence (Museo Archeologico Nazionale 277). The outer garments worn by Florence 277 and 76.AO.85.2 both display a decorated band on the front edge. Emeline Richardson noted the unusual style of the bronze figure, including her unique banded scarf, and compared the work to a group of Greek-Ionian-looking bronzes, her Tomba del Barone group, named after the eponymous Tarquinian tomb. Richardson dated Florence 277 to the end of the sixth century B.C.1 The amber’s hairstyle, however, is different from that worn by most other Archaic Etruscan human-form figures. It is one found on a number of Greek marble korai, sirens, and sphinxes, and is comparable to that of a unique image, possibly Etruscan, possibly Magna Graecian, of a bronze of a crowned and curiously robed figure from Villa Ruffi, Covignano (Rimini), now in Copenhagen.2

There is a distinct “Greekness” about the physiognomy and style of 76.AO.85.2. This is brought out by comparison to three different marbles: a small head of a sphinx from Aegina in Athens,3 a kore head from Lindos in Copenhagen,4 and a small kouros (unfinished) from Paros in Paris.5 There are especially striking correspondences between the Paris kouros and 76.AO.85.2: the full cheeks, which extend all the way from the angles of the mouth to the edge of the jaw, the form and depth of the nasolabial furrows, the placement of the eyes, and the hair framing the face. These Archaic marbles all date to the second half of the sixth century, with the Paros kouros close to the mid-century mark and the female heads in the later sixth century.6

The hairstyle of 76.AO.85.2, a complex fashioning of overlapping rounded waves, is an ancient one, first found in the Near East for gods and kings and refashioned in Early Archaic art for male and female figures, including sphinxes.

76.AO.85.2 may be the earliest extant representation of a winged amber head-pendant. The wing—growing or attached behind the ear—implies the existence of a symmetrically placed ear on the other side of the head. This is not the only amber head-pendant to have a wing: a number of heads have a wing or wings. 76.AO.85.2 offers the opportunity to consider how an amber carver might address the concept of the head and wings of a winged divinity.

The choice to represent one wing or a pair must have depended on the form of the amber blank. For obvious technical reasons, wings projecting upward from the shoulders would be difficult to represent convincingly. Certain forms inherent in the undulating forms of the raw material might even have provided inspiration for the images: the rounded volute wing of 76.AO.85.2 may have started out as a natural high point on the resin. Other winged amber head-pendants are a pair from the Tomb of the Ambers, Ruvo (Naples);7 a head-pendant in profile to right, with one clearly represented wing, from an amber-rich grave of the Rutigliano-Purgatorio Necropolis;8 a fragmentary head-pendant of a frontal female head with one wing in New York;9 two others in the Getty collection, (cat. no. 23) and (cat. no. 16); a large frontal head with two wings in the Steinhardt collection, New York;10 and three unpublished examples in a London private collection. Many of these winged heads are closely related in artistic style and in manner of dress to other, wingless amber head-pendants.

The wing might well be an attribute of the head, acting as pars pro toto of a divinity, demigoddess, or demon; the winged head might be considered the sculptural compression of a complete winged figure.

The large and disfiguring frontal hole in 76.AO.85.2 was bored through the ear and surrounding area. As noted in the introduction and in the “Pendants in the Form of the Human Head” opening, such large holes are found on a number of other figured ambers, of both male and female subjects, and of complete figures as well as both frontal and profile head-pendants, including satyr head-pendants, female head-pendants, a dancing female, a pair of sirens, a horse head–pendant, and a head of Herakles in a lionskin headdress.11 Was this pendant formerly attached to a fibula, as is the case with a head-pendant excavated at Villalfonsina (Chieti) and the two pins with amber heads threaded on them from Rutigliano, a satyr head on a silver pin and a female head on a bronze pin?12

76.AO.85.2, like the large profile head-pendant of a satyr, (cat. no. 12), has four stopped bores, a plug retained in one of them. Were they part of the original production or made later? All the physical evidence—the smoothed prominent surfaces13 (this is not the typical breakdown of the cortex from oxidation), the multiple through-bores, the abrasion troughs, and the central hole—indicates that this pendant must have been used over a period of time before its final interment. The inherent evidence of 76.AO.85.2 suggests that it served as an important amulet-ornament for the living long before it was finally placed in a grave, perhaps pinned to the funereal dress of a girl or woman, in protection and in “mourning attending the death of the young.”14 The wing, the old-fashioned coiffure, the Etruscan dress, and the style suggest that it was made in an Etruscan ambient where a Greek (perhaps Parian or Greco-Etruscan) artisanal tradition was significant.

Notes

- , pp. 285–86, pl. 198, figs. 669–71. ↩

- Copenhagen, National Museum 4203. The bronze likely records an older image type from Ionia or elsewhere in East Greece, one that looks back to older Oriental models. It is possibly Etruscan and has been compared to the korai of northeastern Etruria; B. Bundgaard Rasmussen in , p. 622, no. 278, makes a convincing suggestion that it is Magna Graecian, perhaps from southern Sicily. ↩

- Athens, National Archaeological Museum 1939. ↩

- Copenhagen, National Museum 12199. ↩

- Paris, Louvre Ma 3101 (circa 540 B.C.): , pp. 80–82, no. 73. Two heads comparable to the kouros, which are finished but are worn, are in the Liebieghaus, Frankfurt (H. von Steuben, Kopf eines Kuros, Liebieghaus Monographie 7 [Frankfurt am Main, 1980]), and in the Iolas collection (C. Rolley, “Tête de kouros Parien,” 103 [1978]: 41–50, figs. 1–7). ↩

- , pp. 60, 77, 98, places the Louvre kouros in his Paros group of the mid-sixth century and the Aegina head with his Chios group, dating it to the later sixth century, and associates the Lindos head with Knidian coinage of the years around 500 B.C. Gisela Richter placed the Lindos and Aegina heads (“kore or sphinx?”) in her Samian Cheramyes Genelaos group, dated to the second quarter of the sixth century, and the Louvre kouros in her Melos group, with a date of about 550 B.C.: , no. 66, figs. 214–16 (Athens head); no. 77, figs 244–47 (Lindos head); no. 116, figs. 356–58 (Paros kouros). ↩

- Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale 113644, 113646 (excavated in 1876). No. 113644 has symmetrical wings; no. 113646 is by another hand and shows a different approach to the subject (it has a single small wing on the right side of the head). These winged heads are two of the five surviving figured carved ambers from the Ruvo tomb. The others are an elongated female head (fragmentary) by still another hand; a piece with an indeterminate subject; and a large pendant of a kneeling warrior, armored with helmet, shield, and sword (no known inv. nos.) and attended by a crow. G. Prisco in I Greci in Occidente: La Magna Grecia nelle collezioni del Museo Archeologico di Napoli, exh. cat. (Naples, 1996), pp. 114–16, figs. 10.5–9, identifies the warrior pendant as Achilles, and dates it to the end of the sixth or beginning of the fifth century B.C. For a possibly relevant interpretation of Achilles in relationship to the cult of Apollo, see . An amber Achilles pendant would be a powerful apotropaion, the color of the amber reinforcing the potency of the martial subject. ↩

- Taranto, Museo Archeologico Nazionale 138144 (from the male Tomb 9, fifth century B.C.). ↩

- New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art 23.160.97: , p. 32, fig. 100. ↩

- New York, collection of Michael and Judy Steinhardt: , p. 151; and , pp. 289–90, fig. 5. ↩

- Tomb 9, Rutigliano-Purgatorio Necropolis (Taranto, Museo Archeologico Nazionale 138144: Ornarsi d’ambra: Tombe principesche da Rutigliano, ed. L. Masiello and A. Damato [Rutigliano, 2004]; , p. 131, n. 408; and G. Lo Porto in Locri Epizefirii: Atti del XVI Convegno di studi sulla Magna Grecia [Naples, 1977], pl. CXV). On the subject of pendants with large secondary holes see “The Working of Amber,” in the introduction, n. 266. ↩

- The head-pendant from Villalfonsina, pierced through the top of the hair, dangles from the pin of the fibula: , pp. 314–15; R. Papi, “Materiali archeologici da Villalfonsina (Chieti),” 31 (1979): 83–85, 91. The head-pendants from Tomb 9 (satyr) and Tomb 10 (female) from the Rutigliano-Purgatorio Necropolis are discussed in the introduction. ↩

- The touching, rubbing, and kissing of faces in prayer, adoration, propitiation, warding away danger or evil, and communication of other kinds are the subject of an enormous body of literature. See the introduction, particularly n. 176. ↩

- Diodorus Siculus, Library of History 5.23–24: amber “is commonly used in connection with the mourning attending the death of the young.” ↩

Bibliography

- Croissant 1983

- Croissant, F. Les protomés féminines archaïques: Recherches sur les représentations du visage dans la plastique grecque de 550 à 480 av. J.-C. 2 vols. Paris, 1983.

- Grimaldi 1996

- Grimaldi, D. A. Amber: Window to the Past. New York, 1996.

- Hamiaux 1992

- Hamiaux, M. Les Sculptures grecques: Musée du Louvre. Vol. 1. Paris, 1992.

- Mastrocinque 1991

- Mastrocinque, A. L’ambra e l’Eridano: Studi sulla letteratura e sul commercio dell’ambra in età preromana. Este, 1991.

- Negroni Catacchio 1999

- Negroni Catacchio, N. “Alcune ambre figurate preromane di provenienza italiana in collezioni private di New York.” In Koina: Miscellanea di studi archeologici in onore di Piero Orlandini, edited by M. Castoldi, pp. 279–90. Milan, 1999.

- Negroni Catacchio 1975

- Negroni Catacchio, N. “Le ambre garganiche nel quadro della problematica dell’ambra nella protostoria italiana.” In Civiltà preistoriche e protostoriche della Daunia: Atti del colloquio internazionale di preistoria e protostoria della Daunia, Foggia, Italia, 1973, pp. 310–19. Florence, 1975.

- Richardson 1983

- Richardson, E. H. Etruscan Votive Bronzes: Geometric, Orientalizing, Archaic. 2 vols. Mainz am Rhein, 1983.

- Richter 1940

- Richter, G. M. A. Handbook of the Etruscan Collection. Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, 1940.

- Richter 1968

- Richter, G. M. A. Korai. London, 1968.

- Simon 1998

- Simon, E. “Apollo in Etruria.” Annali della Fondazione per il Museo “Claudio Faina” 5 (1998): 119–43.

- Torelli 2000

- Torelli, M., ed. Gli Etruschi. Exh. cat. Venice, 2000. Published in English as The Etruscans. Milan, 2000.