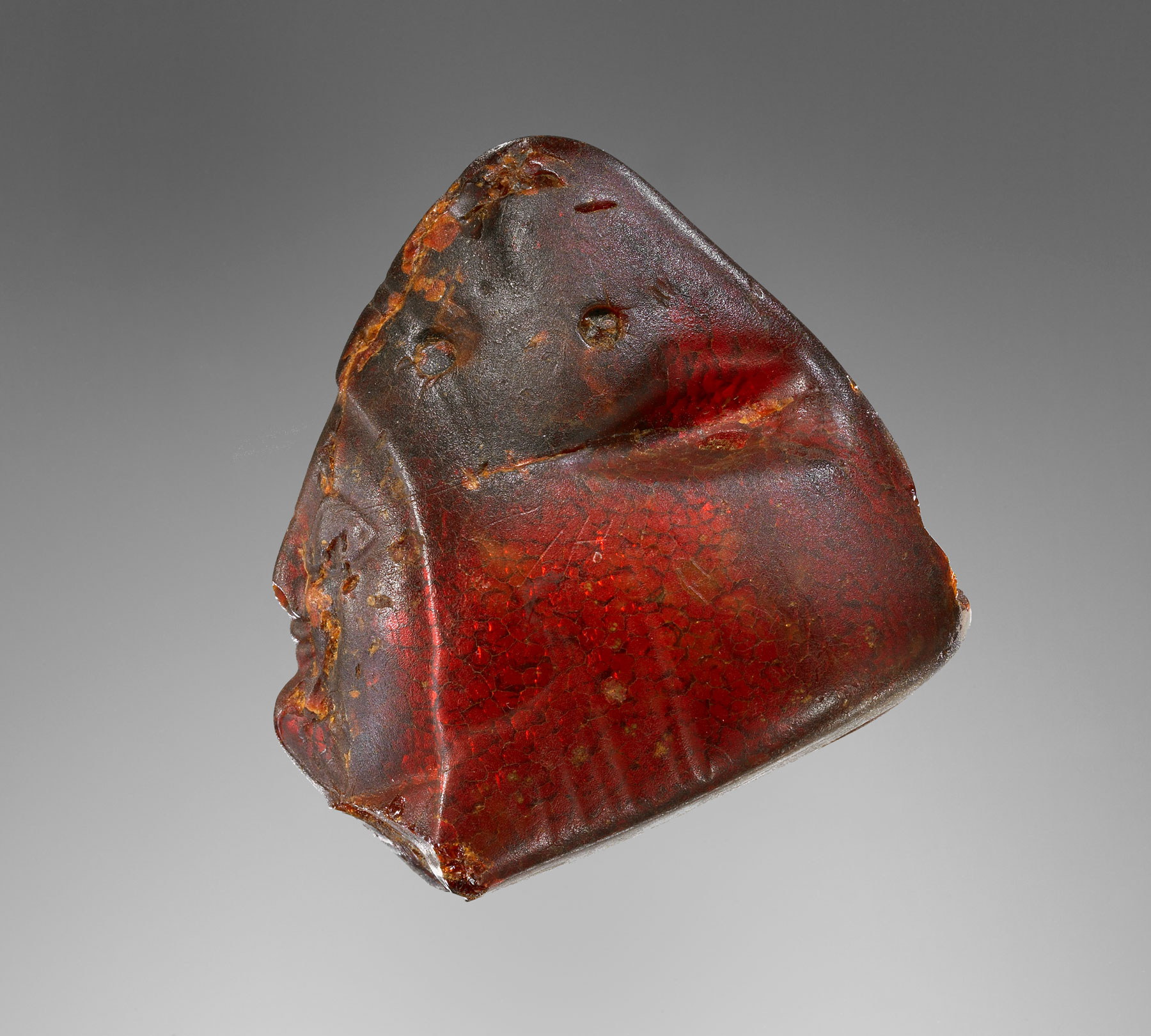

14. Pendant: Female Head in Profile

| Accession Number | 77.AO.81.4 |

| Culture | Etruscan |

| Date | 525–480 B.C. |

| Dimensions | Height: 57 mm; width: 56 mm; depth: 30 mm; Weight: 49.8 g |

| Subjects | Jewelry |

Provenance

–1977, Gordon McLendon (Dallas, TX), donated to the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1977.

Condition

The piece is in a good state of preservation. The surface is smooth and firm, despite a number of recent as well as older (weathered) small breaks and chips. There are fissures extending from the apex of the headdress to the eye, and from under the eye to the corner of the mouth. All fissures and cracks contain yellow-ocher residue. The smoothing of the prominent surfaces (a wear pattern different from overall erosion); the patination covering some of the breaks, including on the tip of the nose, the lower edge of the eye, and several places on the cheeks; and wear on the suspension perforations are likely evidence of use wear. The amber is opaque in ambient light and reddish in color. With transmitted illumination, the interior appears bright orange and is transparent. There is a cloudy inclusion (possibly bubbles) at the top of the headdress.

Description

The shape of the pendant is nearly triangular. The obverse is rounded and the carving curves around the form of the amber except on the back, which is plain but uneven in surface. The figure is wearing a conical cap, and over it a veil and another overgarment. She also wears a circular earring. No hair is showing. The face is set off from her neck by an indentation. Her eye is large and almond-shaped, and is set off from the plane of the face by a continuous filletlike line, which represents the eyelids. The nose follows the same plane as the brow, with only a slight indention for the root. The upper lip area is short, and the barlike lips are pulled into a smile. The lower lip is wider than the upper. The horizontal sulcus is shallow and the chin prominent. The under-chin is fatty. The point of the chin extends forward, to the level of the tip of the nose. The neck is plump.

The uppermost layer of clothing, a shawl or the top portion of a cloak, covers a conical hat and veil. The grooves parallel to the edge of the overgarment are perhaps its border or the imprint of the edge of the hat beneath. The veil’s front border is finished with a band, represented by fine parallel lines. Five soft, narrow grooves represent the fabric’s folds as it hits the shoulder area. A shallow indentation in the overgarment, at about the jawline, indicates a break in the fall of the fabric.

When suspended, the head would have hung with the chin forward; an imaginary line drawn from the tip of the nose to the chin would have been perpendicular to the ground. The slope of the forehead and the slope of the chin would have been at approximately 60 and 120 degrees to the perpendicular.

On the reverse is a deep groove, probably a cleaned fissure. A 3 mm perforation for suspension extends from the flat area on the bottom side of the pendant and exits at the deep cleft on the side of the headdress. There are two bores stopped with amber plugs: one is located on the upper part of the headdress, and a second, 3 mm in diameter and about 11 mm deep, is under the chin.

Discussion

This head-pendant has no exact parallel. The pendant’s triangular shape is unique. The dress of the figure, however, is similar to that worn by (cat. no. 15). Moreover, there are several parallels for the physiognomic type and the style of the pendant. 77.AO.81.4 is related to a number of images of women from Samos and other Ionian centers of the third quarter of the sixth century B.C. Although the comparison can be made only from an old photograph, 77.AO.81.4 is remarkably similar to a now lost (unfinished) head once in Berlin, which was uncovered in the Heraion at Samos.1 The pendant also is akin to a family of East Greek terracottas. Other pertinent parallels include two mid-sixth-century alabastra in Paris and London, and a half-figure statuette of the second half of the century in Copenhagen.2 Although the chin of 77.AO.81.4 is more prominent than those of the terracottas, their other morphological similarities are compelling.

Still closer comparisons are to be found in Etruscan art. For the dress of 77.AO.81.4, the most striking parallel is the Etruscan bronze votive in Florence (Museo Archeologico Nazionale 277), which belongs to Emeline Richardson’s Tomba delle Barone group, one she characterizes by its Ionian associations. (Florence 277 is discussed in more detail in the entry for ). An amber head-pendant in London (British Museum 53) wears similar dress, although her veil is drawn more tightly in front and forms stronger horizontal folds.3

For the style of 77.AO.81.4, other Etruscan small bronzes and bronze reliefs are instrumental in situating the amber. Three figures (Peleus, Thetis, and a female companion) in one of the panels of the Loeb Cauldron C are very similar in physiognomy and expression, although their eyes are smaller and their hairstyles different.4 Eight small bronzes are important comparisons for both the iconography and the style of 77.AO.81.4. They are an Etruscan votive in Paris (Bibliothèque nationale, Cabinet des Médailles 204); the four bronze corner figures from the box of a carpentum, now dispersed among Perugia, Munich, and Paris;5 two “Latin” bronzes from Satricum in the Villa Giulia (Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia 10519 and 10922); and a “Latin” bronze in the Bibliothèque nationale, Paris (BN 205).6 The Villa Giulia bronzes are distinguished by the fact that they wear the Ionian chiton properly understood (a rare feature; they are draped like the Samian sisters from the Genelaos dedication), and by the upright solar disk at the back of their heads. Richardson considers them images of the Mater Matuta, the goddess of daylight and a light bringer.7 The figure of BN 204 is unusually pretty and her unusual dress uncommonly delicate: she is wearing an unbelted chiton, and her hairstyle is otherwise unknown in the Middle Archaic period.8 The profiles of 77.AO.81.4 and BN 204 are so alike as to be from the same model, or to be products of the same ambient: the angles of the nose and the chin relative to the perpendicular are the same. BN 204 might even allow us to imagine how 77.AO.81.4 would have looked in full face: that is, wide through the temples, with eyes slightly far apart, and narrowing to the chin.

Who or what might 77.AO.81.4 represent? She wears a large earring and elaborate dress: cap, veil, and overgarment. Not one strand of hair is showing. At the least, this is the adornment of the elite. Does this indicate the figure’s maturity or outdoor activity, two explanations offered for head coverings in Greek sculpture? On the other hand, does the dress indicate religious-political activity (for example, sacrifice or attendance at another ritual)? The material precludes that the representation is that of a mortal; it signals, rather, that the image is that of a heroic, divine, supernatural, or demonic being. If a divinity, then perhaps it is one whose powers were connected to the sun and to its regenerative powers. The Ionian dress and style of the head, too, may indicate something of its identity, as well as saying something about where, why, and by whom 77.AO.81.4 was carved and used. The style and dress point to South Ionia, Etruria, and “Latin” Etruscan imagery.

77.AO.81.4 could represent a divinity of light, similar to the Latin Juno Licina or the dawn goddess Mater Matuta, both of whom share some aspects of the Greek Artemis (perhaps in her guise as Artemis Phosphoros), notably midwifery. Since the dawn is also a potent symbol of new life, this may be a South Ionian Eos or the Etruscan Thesan. Two other alternatives are Artumes and the Latin Juno Gabina; Richardson records that bronzes of a “Latin” type, some of them wearing sun disks, have been found at Gabii, near the so-called temple of Juno Gabina.9 If 77.AO.81.4 does indeed represent a light and life divinity, one that might be called upon with some regularity for aid in childbirth, in protection, or in the care of young children, such an identity may help explain the use wear on the face of the pendant.

Notes

- Berlin, Staatliche Museen 1875: , no. 157, figs. 504–5; , p. 41, no. 18, pl. 10. ↩

- Paris, Louvre MC681; London, British Museum 60.44.57; Copenhagen, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek 949. ↩

- , p. 71, no. 53, pl. XXII. ↩

- See . ↩

- See discussion by S. Bruni in , p. 581. ↩

- , pp. 21–23, 26–67, 361. ↩

- Ibid., p. 265, pls. 605–6. ↩

- E. Richardson, “Moonéd Ashteroth?,” in In Memoriam Otto J. Brendel: Essays in Archaeology and the Humanities (Mainz, 1976), pp. 21–24. See also , pp. 461–62. ↩

- , p. 265, pls. 605–6. ↩

Bibliography

- Freyer-Schauenburg 1974

- Freyer-Schauenburg, B. Bildwerke der archaischen Zeit und des strengen Stils: Samos. Vol. 11. Bonn, 1974.

- Höckmann 1982

- Höckmann, U. Die Bronzen aus dem Fürstengrab von Castel San Mariano bei Perugia: Staatliche Antikensammlungen München, Katalog der Bronzen. Vol. 1. Munich, 1982.

- Richardson 1983

- Richardson, E. H. Etruscan Votive Bronzes: Geometric, Orientalizing, Archaic. 2 vols. Mainz am Rhein, 1983.

- Richter 1968

- Richter, G. M. A. Korai. London, 1968.

- Strong 1966

- Strong, D. E. Catalogue of the Carved Amber in the Department of the Greek and Roman Antiquities. London, 1966.

- Torelli 2000

- Torelli, M., ed. Gli Etruschi. Exh. cat. Venice, 2000. Published in English as The Etruscans. Milan, 2000.

- Waarsenburg 1995

- Waarsenburg, D. J. The Northwest Necropolis of Satricum: An Iron Age Cemetery in Latium Vetus. Amsterdam, 1995.