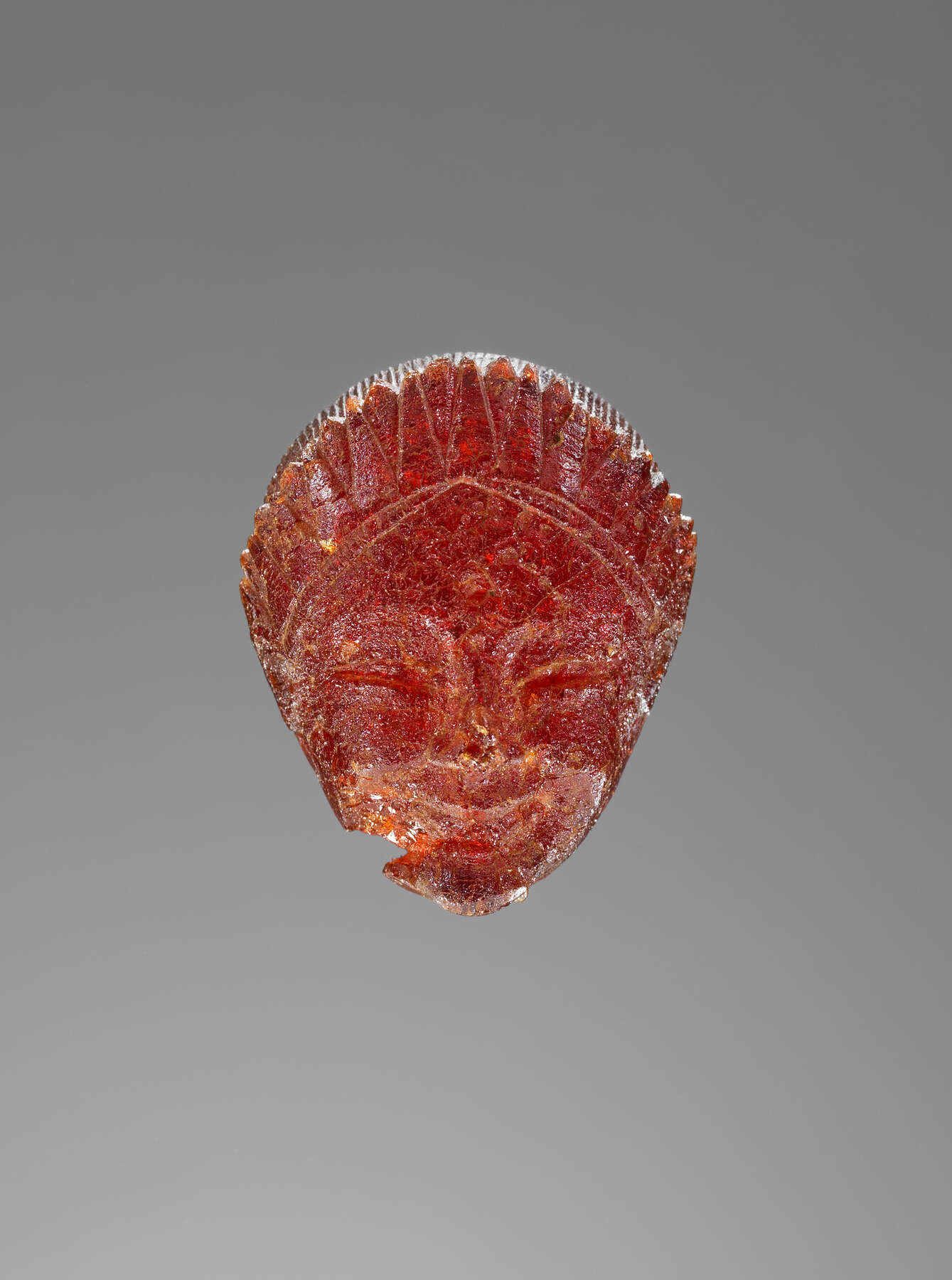

13. Pendant: Satyr Head

| Accession Number | 82.AO.161.1 |

| Culture | Etruscan |

| Date | 525–480 B.C. |

| Dimensions | Height: 53 mm; width: 48 mm; depth: 16 mm; Weight: 11 g |

| Subjects | Dionysos, cult of (also Satyr); Jewelry |

Provenance

–1982, Jiří Frel, 1923–2006, and Faya Frel (Los Angeles, CA), donated to the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1982.

Condition

The piece is intact, although the surface condition is poor and the surface is covered by a thick, flaking yellow alteration crust. There are also many small chips on all sides. There is a large fissure on the top of the head and smaller fissures on the reverse side. A whitish encrustation covers some areas. The amber is yellowish brown and opaque in ambient light, translucent and orange where the interior is exposed by modern breaks, and bright orange and generally translucent in transmitted light. There are inclusions or deteriorated material visible in the fissures.

Description

This relatively large head is egg-shaped in front view and is like a rounded slab in profile view. It is slightly convex on the obverse, flat and plain on the reverse. Despite the poor condition of the piece, its subject is still legible. The hair is caplike, delineated by eleven rows of snail-like curls in even rows. The head is widest at the position of the ears. Traces of the right eyebrow remain; the brow itself is wide and smooth. The plastic, almond-shaped eyes are located equidistantly between the top of the head and the chin. The inner and outer corners (canthi) appear to be on the same line. Although broken, the ears are long, pointed, and prominent and are set high up on the head. The cheeks are wide and flat and the face long. The remains of the nose suggest that it was small and short. The mouth area is small and surrounded by a short mustache and low, close-cropped beard.

There are two suspension perforations, a narrow-gage lateral bore through the top of the head and a second, larger, rostrocaudal hole in the center of the forehead. All four exits show enlargement at the upper parts, abrasion troughs, and chipping. There is a stopped bore in the top left of the head. When suspended from the lateral bore, the head hangs with the brow tipped forward and the chin recessed. Suspended from the large hole, the head hangs perpendicular to the ground. If the large hole were used to secure the head to a support, its chin would have been back, the top of the head forward.

Discussion

The condition of this head—the evidence of pulling on the upper edges of the perforations, the frontal perforation that is likely secondary to the lateral bore, and the wear on the prominent surfaces of the head—suggests that it saw substantial use before it was buried. A number of pre-Roman figured ambers have a narrow-gage transverse perforation for stringing and one or more large front-to-back borings. Some have been found still attached to fibulae. Others retain only metal nails, or their traces (some bronze, others silver), perhaps used to attach the amber onto a wood (or other material) support. There are other significant examples of figured ambers with both narrow-bore lateral perforations and larger front-to-back borings.1 They include a female head from Rutigliano still attached to a silver fibula, documented as from the early fifth century B.C.; a dancing figure from Oliveto Citra, which was first perforated with a transverse hole for suspension as a pendant and then with five front-to-back holes, one large one in the middle and four slightly smaller holes surrounding it; a fragmentary female dancer (probably once joined by a male figure) in a New York private collection, which has a transverse perforation and four large holes with the remains of bronze rivets; and two profile female head-pendants and a horse’s head on the London art market (perhaps from the same findspot), whose frontal holes still retain silver nails. In each case, the large rostrocaudal holes are disfiguring and appear to be secondary to the lateral suspension bores, which are worn from pulling, with characteristic abrasion troughs on the upper inside edges of the exits.

The Getty Satyr’s Head is illuminated by comparison with six female-subject head-pendants in the British Museum: BM 55, whose findspot is unknown, and five bequeathed by Sir William Temple, which are said to have come from Armento (BM 54, 56, 57, 58, and 60).2 82.AO.161.1 is most like BM 57, a head of a female figure wearing a feather crown.3 The London heads and this amber satyr have a distinctive softness in the modeling, especially in the planar transitions, which must have been accomplished by abrasion. This is contrasted with the outlining of the eyes, probably done with a use of a graver, and with the description of the hair, perhaps accomplished with a carving tool such as those used for ivory or wood. The visual effect is more like stone carving and the best of ivory working or fine woodworking, and less like that of gem engraving. Donald Strong suggested that the London head-pendants, though said to have been found at Armento, were very likely made in Campania or “under the strong influence of Campanian art of the sixth century BC.”4 A comparison of the London pendants to selected Campanian coroplastics bears out Strong’s observations.5 Marked, too, are the East Greek aspects of 82.AO.161.1 and the London group; this is highlighted when they are compared to East Greek sculpted and molded works, and to the most East Greek–looking of Etruscan bronzes and painted vases.6

82.AO.161.1 has stylistic and iconographical features in common with (cat. no. 10), attributed to an East Greek or East Greek–trained carver. Many of the comparanda important for also elucidate 82.AO.161.1. In addition to these are coins and glyptics with frontal faces of Dionysos and his male followers. Three key comparisons are the “satyr” of an early electrum hecte from Cyzicus;7 the device of a reclining satyr on an agate scarab in London, the name piece of the Master of the London Satyr, an East Greek carver working in Etruria;8 and the Dionysos wrapped around the back of the cornelian pseudo-scarab in Boston, the name piece of the Master of the Boston Dionysos.9 (The work of the Boston Master is very close to that of , cat. no. 12.) A number of satyr heads on Attic black-figure vases are also important comparanda for the above-listed images of satyrs in amber: the large and staring eyes and the carefully groomed hair and beards are but two of the striking similarities.10

The only other amber satyr head related in format and size to 82.AO.161.1 is a well-preserved pendant from Tomb 106 in the necropolis at Braida di Vaglio (Basilicata).11 Although the Braida amber differs in the satyr type, the face exhibits the same sober expression. The Braida satyr’s hair is deeply waved around the brow, his beard long, and his large ears prominent. This is in contrast to the short beard, small ears, and curly hair of the Getty satyr. The context of the Braida satyr pendant is the early fifth century B.C., but it must have been carved earlier, perhaps as early as the third quarter of the mid-sixth century. It also shows considerable use wear and secondary working. The face is especially worn on the prominent surfaces, and the inserted suspension loop in the top of the head is likely secondary to the narrow-gage lateral boring. The same British Museum heads presented above as comparisons for 82.AO.161.1 are also instructive for the Braida di Vaglio satyr, especially BM 56.

For a discussion of the iconography of a satyr in amber, see the entry for Satyr Head in Profile ().

Notes

- This group is discussed in “The Working of Amber” in the introduction, n. 266. ↩

- BM 58, which is carved fully in the round, appears to be the earliest of the group: see , pp. 71–73, no. 58, pls. XXIII–XXIV. ↩

- Ibid., p. 73, no. 57, pl. XXIII, bears a resemblance to images of Hathor wearing a feathered crown, although her ears are human, not bovine. Strong describes the eyes of BM 57 as carefully worked and large in proportion to the other features. This head in London is also discussed in the entry for . ↩

- Ibid., p. 73. ↩

- See ; ; and W. Johanowsky, Materiali di età arcaica dalla Campania (Naples, 1983), pp. 72–73. ↩

- This is borne out by a comparison of British Museum 58 with a small marble head from Miletos in the Louvre (Ma 4546): , no. 49 (circa 520–510 B.C.). The marble’s squarish face and strong jaw, upward cant of the eyes, serious expression, waved hair at the brow, and crown, which encircles the head, are all similar to BM 58. ↩

- See , no. 5. ↩

- London, British Museum 465. For the Master of the London Satyr, see , pp. 153, 181, 420 (with earlier bibl.). ↩

- See entry for . ↩

- For the relevant satyr heads on Attic black-figure vases, see, for example, , pp. 169–70; , p. 97, n. 93; G. Ferrari, “Eye-Cup,” 1986: 520; ; and E. E. Bell, “Two Krokotos Mask Cups at San Simeon,” University of California Studies in Classical Antiquity 10 (1977): 115. Carpenter cites the amphorae with heads listed in 275 and examples of cups with satyr heads in the Group of Walters 48.42: see , nos. 15, 206. ↩

- Potenza, Museo Archeologico Nazionale “Dinu Adamesteanu” 96684: , p. 117; , p. 66, no. 311 (satyr), fig. 37. The satyr head-pendant is discussed in the introduction and in the entry for . ↩

Bibliography

- Boardman 2001

- Boardman, J. Greek Gems and Finger Rings: Early Bronze Age to Late Classical. New and enlarged ed. New York, 2001.

- Bottini and Setari 2003

- Bottini, A., and E. Setari. La necropoli italica di Braida di Vaglio in Basilicata: Materiali dallo scavo del 1994. With appendix by M. Torelli. 60, serie miscellanea 7. Rome, 2003.

- Carpenter 1986

- Carpenter, T. H. Dionysian Imagery in Archaic Greek Art: Its Development in Black-Figure Vase Painting. Oxford, 1986.

- Mottahedeh 1979

- Erhart [Mottahedeh], K. P. The Development of the Facing Head Motif on Greek Coins and Its Relation to Classical Art. New York, 1979.

- Hamiaux 1992

- Hamiaux, M. Les Sculptures grecques: Musée du Louvre. Vol. 1. Paris, 1992.

- Hedreen 1992

- Hedreen, G. M. Silens in Attic Black-Figure Vase-Painting: Myth and Performance. Ann Arbor, 1992.

- Magie d’ambra 2005

- Magie d’ambra: Amuleti e gioielli della Basilicata antica. Exh. cat. Potenza, 2005.

- Riis 1938

- Riis, P. J. “Some Campanian Types of Heads.” In From the Collections of the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek,, vol. 2, pp. 140–68. Copenhagen, 1938.

- Riis 1981

- Riis, P. J. Types of Heads: A Revised Chronology of the Archaic and Classical Terracottas of Etruscan Campania and Central Italy. Copenhagen, 1981.

- Strong 1966

- Strong, D. E. Catalogue of the Carved Amber in the Department of the Greek and Roman Antiquities. London, 1966.