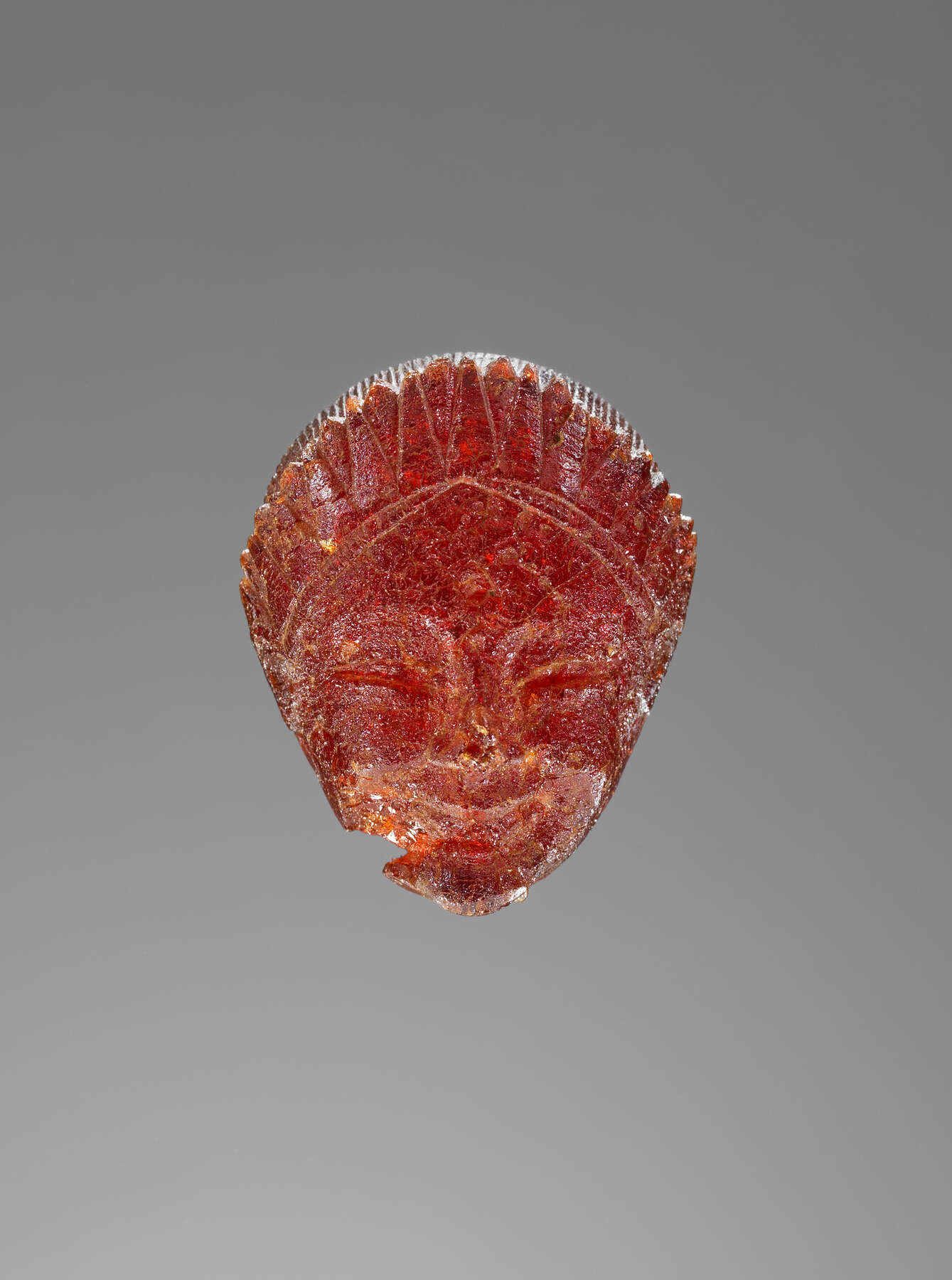

11. Pendant: Head of a Female Divinity or Sphinx

| Accession Number | 76.AO.79 |

| Culture | Etruscan |

| Date | 550–525 B.C. |

| Dimensions | Height: 34.5 mm; width: 24 mm; depth: 16 mm; Weight: 7.7 g |

| Subjects | Ionia, Greece (also Ionian, Greek); Jewelry; Sphinx |

Provenance

–1976, Gordon McLendon (Dallas, TX), donated to the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1976.

Condition

There are no visible inclusions. The overall condition is good; the surface is firm and stable, although an extensive crack network is visible in transmitted light. There are small chips above the left eyebrow, near the left eye, and on the left side of the hair that join to form a fine diagonal crack; there are tiny losses on the right cheek and right ear. There are small chips and losses on the back of the object. It is red-brown and opaque in ambient light and bright orange in transmitted light. The metal insertions (wire or pins?) in the top of the head are broken off; one is rectangular in cross section. (They have not been scientifically analyzed but appear to be of silver.)

Description

The amber is convex on the obverse; the reverse is smooth and curved so that in profile to right, the back is C-shaped. Only the front of the head is depicted—that is, the face and the front part of the hair. The eyebrow ridges lie flat on the surface of the face; the upward curves are slight (the left somewhat more curved than the right), with a delicately suggested transition to the root of the nose. The shallow, feather-shaped eye sockets (which may have been intended for inlay) incline sharply upward at the upper corners. The lids are indented at the inner canthi, swelling above the eyes with the lids overhanging the lower rims. The area under the lower lid is sensitively modeled around the shape of the eye itself. The cheeks are full, especially around the mouth area.

The head’s facial features are not precisely symmetrical: the right eye turns up more at the outer canthus, its inclination more manifest, while the nose lists slightly to the right, its right nostril higher. The smallish nose sits close to the frontal vertical plane of the face. Straight and tipped upward, the wings of the nose are somewhat fleshy, with the nares clearly defined. The mask has bow-shaped lips, the upper one overlapping the lower one, that are slightly pointed at the center, and the corners of the mouth are tucked in, to create the impression of a slight smile. The mentolabial sulcus is deep. The chin is wide and rounded, jutting forward to the plane of the brow. In full-face view, the ears are hardly noticeable, but in side view, they are clearly defined. They are large and placed high on the head. The antihelices are indicated, the antitraguses not indicated, and the lobes are separate.

The back is less polished than the front. There are traces of abrasion around the circumference and on the reverse. The individual strands of hair were cut with a graver. There are the remains of three metal inserts (silver?) in the top of the head, the central one larger than the two flanking it, and the residue of a green (bronze) corrosion product on the reverse.

Discussion

76.AO.79 has no exact parallel. No conclusion may be drawn about the sex, function, or identity of the figure. It is not drilled for suspension, nor is there a mount; it has a curved back; and the green (bronze?) corrosion product on the reverse appears to be the result of direct contact with metal. The metal inserts in the top of the head are placed in the position of a crown, and although a suspension device could have been incorporated, there is no apparent parallel for this method.

76.AO.79 was accessioned as the head of a girl and published in 1993 by this author as that of a male divinity. If this latter identification holds true, the divinity could be Apollo. The sexing of the head now seems less sure; it may be that the original designation was the correct one. If 76.AO.79 indeed represents a female figure, the amber may represent a “brilliant” divinity such as Artemis or Aphrodite, Potnia Theron, or perhaps a beautiful sphinx.

In form, 76.AO.79 is related to the previous catalogue entry, (cat. no. 10). They both have curved backs, although that of 76.AO.79 is curved on one plane only and is not rounded. The one other amber head-pendant that has a similar curved back is a female head-pendant in Munich.1 It, too, has no visible boring for suspension; instead, the Munich head has a metal (bronze?) suspension loop (of uncertain date) inserted in the top of the amber.

The purpose of the three metal (silver?) inserts in 76.AO.79 may have been to suspend the head, but since there are three, two small and one large, it is more likely that they are the remains of a crown or other head decoration (silver would suit such an ornament).2 Although unlikely, an incorporated suspension loop should not be ruled out. The only parallel for such added decoration is a head-pendant of a female figure (a siren?) in London (British Museum 60), said to be from Armento and probably dating to the mid-fifth century B.C. Metal remains (silver? wire or pin?) are in the lateral suspension boring, and further remains are in a larger vertical boring in the top of the head.3

The curved back of 76.AO.79 and the green residue on it make difficult a hypothetical reconstruction of any support. Contemporary mounted scarabs, amber scaraboids, and gemstones have characteristically flat backs. It is possible that the head was fitted with a gold bezel, comparable to the way that an Etruscan mounted three Egyptian faïence pataikos figures for a necklace.4 However, the corrosion product on the back of 76.AO.79 suggests it was in direct contact with bronze. If the amber was set into bronze, the bronze support would have had to fit the curve of the amber’s back. (Could it have been set into the base of a vessel handle?)5 All other extant amber faces used as inlay are flat on the back, and all are mounted in amber, ivory, or bone.6

If the mounting of the Munich pendant is original, when suspended against a flat surface, the head would appear to look upward; however, if it were the single pendant of a carrier and worn high on the neck at the jugular notch, the amber would have fit snugly into the depression and the mask would have looked straight out. There are many Archaic illustrations of figures male and female wearing simple necklaces with one pendant (or a few) at this position or even higher up, as a choker. Might the same be true of 76.AO.79?

For the style of the head, the best comparison for 76.AO.79 among amber carvings is the Getty amber kore pendant (cat. no. 8), which is attributed to a South Ionian carver. Both compare well with a number of Archaic East Greek sculptures in terracotta and marble, especially those from the ambient of Miletos. 76.AO.79 shares the general stylistic qualities of the Milesian school—the frontality, the horizontality, the solidity, the “Massigkeit”—as outlined by François Croissant. He convincingly demonstrated that there are two great artistic tendencies in Milesian sculpture, a “style graphique” and a “style pictural.”7 It is within this latter trend, within the naturalistic vein of Milesian art, that 76.AO.79 seems to find its proper berth.

76.AO.79 can be linked to specific Milesian works, especially the terracotta protomes of Croissant’s Type B3–B6 series.8 They have in common a relatively flat face, the nose at a low angle relative to the cheeks, a short and overlapping upper lip, and a short, squarish chin. The amber head also compares well with a number of marbles from East Greece: the head of a draped woman from near Ephesus in London (British Museum B89); a siren in Copenhagen, from near Cyzicus; the head of a sphinx from Keramos, in İzmir; and the Louvre Dionysermos.9 The Keramos marble is closest. The head shape, the plastic transitions from area to area, the sweet smile, the air of quiet self-confidence, and the composition of the features are very alike. The relation of the eyes to the eyebrow arcs is the same.

The eye shape is a distinguishing feature of the amber. The eyes of 76.AO.79 are akin to those of many of the terracottas in Croissant’s Samian and Milesian groups, South Ionian marbles, and the Getty amber Kore, but the best parallel is the large ivory “Artemis” from the Halos deposit at Delphi.10 Her distinctive eyes are feather-shaped, turned up at the outer corners, swelling in the center, with the lids stretched over the orbit and the upper lid overhanging the lower and drooping slightly. (Those of 76.AO.79 turn up more sharply, are spaced farther apart, and are even narrower and smaller in proportion to the face.) This affinity is noteworthy not only because it establishes a stylistic connection between the amber and ivory but also because it offers further evidence for the argument that amber carvers worked ivory and vice versa.

The hair of 76.AO.79 is elaborately dressed: the front sections are combed forward, apparently secured by a band, and then flipped back toward the crown, forming a series of curved bunches of hair framing the head. The hair sections just above the ears take the form of so-called Ionian wings. Although the hairstyle may have originated in Ionia, it was quickly absorbed in western Greece and in Etruria. Variants are worn by male and female figures in the Archaic period. Such hairstyles are found on the female figures (both heads and caryatids) of a group of terracotta lamps from Magna Graecia, a type that likely originated in the Achaean cities of the Ionian coast, but which was further developed in the colonies of Magna Graecia.11 The hairstyle of 76.AO.79 is analogous to those worn by certain sirens and sphinxes. The hair of the marble siren from Cyzicus (Milesian work?) in Copenhagen, a number of Etruscan stone sphinxes from Vulci, and the sphinxes of a gold fibula from Vulci in Munich allow the possibility that 76.AO.79 represents an Etrusco-Ionian version of the fantastic creatures.

An exotic comparison is the Tridacna squamosa shell made into a female figure (siren?) by a Syro-Phoenician(?) artisan; an example in the British Museum excavated at Vulci.12 The face carved into the shell’s umbo is very like that of 76.AO.79.

The comparisons presented above point to a date for the head in the period of circa 550–520 B.C. and to a skilled carver from East Greece, perhaps in Etruria, where the impact of artisans from South Ionia and elsewhere in the east had such impact on art in the second half of the sixth century. Whether 76.AO.79 was originally the inlay (face) of a figure in another material or the centerpiece of a pendant, the amber itself determines that the subject of the head is a divine or heroic figure, a supernatural or a demonic being. The metal attachments, if they are part of a headdress and of silver, do not allow another interpretation.13 As Brunilde Ridgway has argued, the very presence of elaborate head decorations in Archaic art “serves to indicate superhuman or divine beings.”14 As she concludes, “The metal attachments on the heads of Archaic statues should be read as part of elaborate headdresses functioning as attributes and helping in the identification of the figures.”15

If the head represents a siren or a sphinx, 76.AO.79 would be another example in amber of the liminal creatures. Whether their images were worn in life or in the grave, the “work” of these creatures was established: they were effective in protection and aversion, and in the journey to the afterworld, both were reputed guides. Both have regenerative aspects. If 76.AO.79 is the head of a female divinity, it may be the image of Artemis or another deity with solar aspects. Then again, if it represents a youthful male divinity, the amber head may denote Apollo. The head, as a glittering object in the form of a divine or demonic being carved with the greatest skill and detail in high-status materials, amber, silver, and perhaps ivory for the eyes, was worthy of the attention of the gods; it is, it was, a marvel to behold. The materials, the image, the exquisite craftsmanship—all were worthy of the gods’ attention. During funerary rituals and in the tomb, 76.AO.79 could have played a small but important role. A shining tear crafted into the form of a beautiful, youthful face was surely appropriate as a funerary gift, especially if the deceased had died young. If the figure is Apollo, it might have brought to mind the stories connecting the solar material, the solar deity, and the mourning by the sun-god for the premature deaths of Phaethon and Asclepius.16

Notes

- Munich, Antikensammlungen 15.003. ↩

- See cat. no. 10, n. 16 and n. 18, for discussion of amber pendants in metal mounts. ↩

- , p. 74, no. 60, pl. XXIV. Strong concludes that the figure is probably female, pointing out that while the hair on the forehead divides like that seen on males, it is bound by a fillet. How the metal element and the caplike hair covering might have functioned together is not apparent. In style, it is very like two of the flying figures from Sala Consilina in the Dutuit Collection, Petit Palais, Paris (see introduction, n. 219). ↩

- See cat. no. 10, n. 17. ↩

- The peculiar form of the back of 76.AO.79 would have allowed it to fit neatly into the indentation of the jugular notch, one of the most vulnerable spots on the body and the place where many early single pendants are represented as hanging. ↩

- The amber pendant from Novi Pazar with an amber mounting is discussed in cat. no. 10, n. 16. Ivory and bone examples are the amber faces of the sphinxes of two Laconian relief plaques, one of ivory, the other of bone, from a kline dating to about 600 B.C., and the now-lost faces of a divinity and her two “acolytes” set into bone plaques from furniture excavated at Belmonte Piceno, dating to the early sixth century. For the bone plaques from Belmonte Piceno, see , pp. 82–85, nos. 135–36, pls. XLIV–XLV, where there is fruitful discussion of the identity (Potnia Theron? Artemis?). For the two sphinx appliqués with amber faces from a couch in the Iron Age Celtic tomb at Grafenbühl, Asperg (Stuttgart, Würtembergisches Landesmuseum), see n. 17 in the “Pendants in the Form of the Human Head” introduction. ↩

- , p. 181. ↩

- Despite the inherent generational transformations in the terracotta series, the profiles of the amber and the terracottas are markedly similar. ↩

- For British Museum B89, see , p. 62 (which he finds to have a rapport with the Milesian school); for the Copenhagen siren (Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek 2817), , pp. 44–45, no. 7; for the Keramos sphinx head (İzmir, Archaeology Museum), , figs. 229–32; , p. 125 (L 53); and , pp. 64, 67, pls. 15–16; for the Paris Dionysermos (Louvre Ma 3600), , pp. 59–60, no. 51. ↩

- Delphi Museum 10413: , no. 33. ↩

- As M. Cipriani (, pp. 122–23) states: “The eclectic character of this production, as cleverly emphasized by Croissant, and the difficulty in isolating specific stylistic elements raise again the more general problem of defining colonial styles.” See F. Croissant, “Sybaris: La production artistique,” in Sibari e la sibaritide: Atti del XXXII Convegno di studi sulla Magna Grecia, ed. A. Stazio and S. Ceccoli (Taranto, 1993), p. 548. This position does not necessarily contradict the Ionian-origin hypothesis of C. Sabbione, “L’artigianato artistico a Crotone,” in Crotone: Atti del XXIII Convegno di studi sulla Magna Grecia, ed. A. Stazio and S. Ceccoli (Taranto, 1983), p. 272. ↩

- For the London shell and further bibliography, see n. 8 in the “Pendants in the Form of the Human Head” introduction. ↩

- A crown of silver, which appears “brighter and more like daylight than gold” (Pliny, Natural History 33.19.9), may, like the amber, establish the figure as divine. The brilliance of the materials and the attention to detail no doubt added to its marvelousness as a work worthy to behold (see “Ancient Names for Amber” in the introduction). ↩

- . See also B. Ridgway, “Metal Attachments in Greek Marble Sculpture,” in Marble: Art Historical and Scientific Perspectives on Ancient Sculpture (Papers Delivered at a Symposium Organized by the Department of Antiquities and Antiquities Conservation and Held at the J. Paul Getty Museum, April 28–30, 1990) (Malibu, 1991), pp. 485–508. ↩

- . ↩

- Apollonius (Argonautica 4.611–18) refers to a Celtic myth that drops of amber were tears shed by Apollo for the death of his son Asclepius when Apollo ventured north in a visit to the Hyperboreans. See “Ancient Literary Sources on the Origins of Amber” in the introduction. ↩

Bibliography

- Akürgal 1961

- Akurgal, E. Die Kunst Anatoliens von Homer bis Alexander. Berlin, 1961.

- Magna Graecia 2002

- Bennett, M. J., and A. J. Paul. Magna Graecia: Greek Art from South Italy and Sicily. Exh. cat. Cleveland, 2002.

- Croissant 1983

- Croissant, F. Les protomés féminines archaïques: Recherches sur les représentations du visage dans la plastique grecque de 550 à 480 av. J.-C. 2 vols. Paris, 1983.

- Hamiaux 1992

- Hamiaux, M. Les Sculptures grecques: Musée du Louvre. Vol. 1. Paris, 1992.

- Johansen 1994

- Johansen, F. Greece in the Archaic Period. Cat., Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek. Cophenhagen, 1994.

- Lapatin 2001

- Lapatin, K. D. S. Chryselephantine Statuary in the Ancient Mediterranean World. New York, 2001.

- Ridgway 1990

- Ridgway, B. S. “Birds, ‘Meniskoi,’ and Head Attributes in Archaic Greece.” 44 (1990): 583–612. Reprinted in B. S. Ridgway, Second Chance: Greek Sculptural Studies Revisited. London, 1994.

- Rocco 1999

- Rocco, G. Avori e ossi dal Piceno. Rome, 1999.

- Strong 1966

- Strong, D. E. Catalogue of the Carved Amber in the Department of the Greek and Roman Antiquities. London, 1966.

- Tuchelt 1970

- Tuchelt, K. Die archaischen Skulpturen von Didyma: Beiträge zur frühgriechischen Plastik in Kleinasien (Istanbuler Forschungen 27). Berlin, 1970.