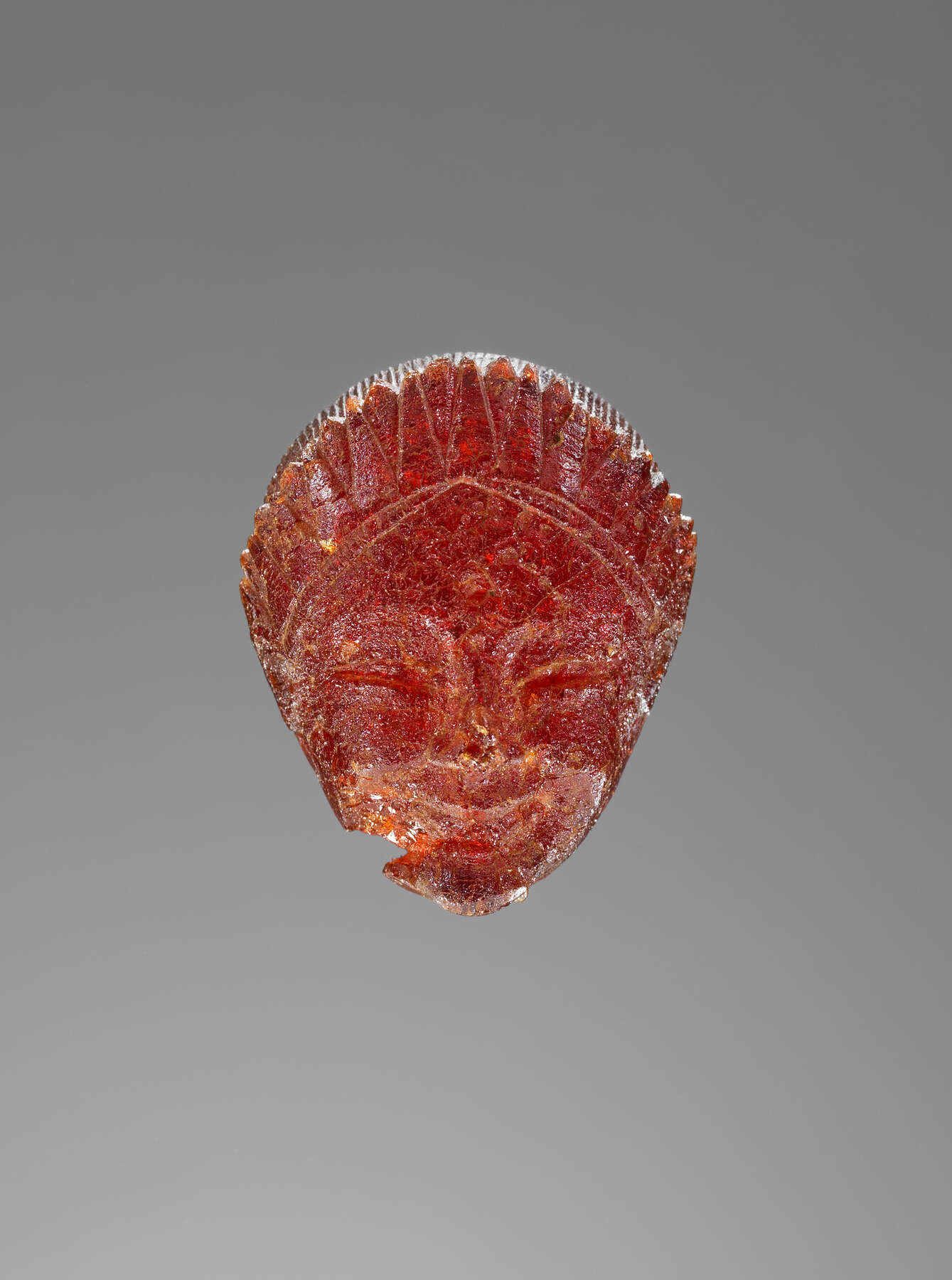

10. Pendant: Head of a Female Divinity or Sphinx

| Accession Number | 76.AO.85.1 and 76.AO.86 |

| Culture | Etruscan |

| Date | 550–525 B.C. |

| Dimensions | Height: 32 mm; width: 26 mm; depth: (face) 12 mm, (back) 5 mm, (joined) 17 mm; Weight: 9 g |

| Subjects | Jewelry; Samos, Greece (also Samian, Greek); Sphinx |

Provenance

–1976, Gordon McLendon (Dallas, TX), donated to the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1976.

Condition

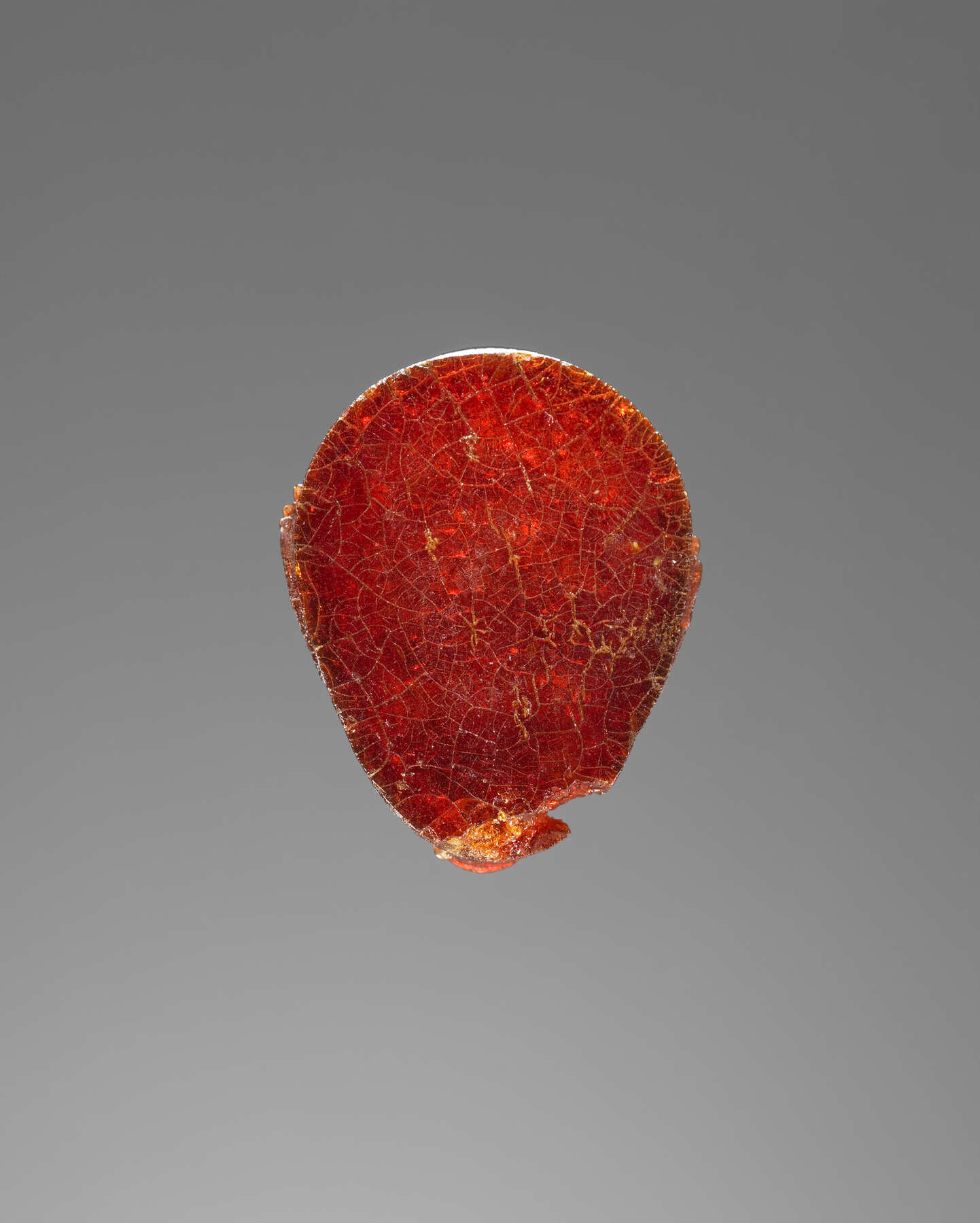

The two sections, 76.AO.85.1 and 76.AO.86, were acquired as separate objects by the donor and accessioned as such into the museum. After their entry into the collection, it was discovered that the two joined and composed one object. Before the donor purchased the pieces, they were cleaned to remove dirt and some encrustation. At the museum, the surfaces were treated with an amber-oil distillate, which made both pieces relatively more translucent but also darker. There are no visible inclusions in either section. The front of the face section, 76.AO.85.1, is in fair condition; it is covered with minute cracks and some chips, and the tip of the nose and a section of the right cheek are broken off. The back of the rear section, 76.AO.86, is in good condition. It retains a high polish on the exterior surface but is marked by opaque spots and tiny fissures, and there is a small loss on the left side. The interior surfaces of both sections are in good condition, with the exception of a small chip at the edge of the inside of the back section. Degraded amber is found in the abrasion scratches of both insides. In ambient light, the amber of 76.AO.85.1 is a deep reddish orange; in transmitted light, it is more transparent and a brighter orange. 76.AO.86 is dark red under strong light and almost opaque in ambient light.

Description

The two parts of the head were joined after being accessioned into the collection. When they are joined, the frontal aspect is an exaggerated egg-shaped oval, widest across the forehead, curved at the headdress, and almost pointed at the chin. In side view, the amber is a flattened oval. The wide forehead is arched at the top, with the brow line mirroring the jawline; the chin is small and pointed, protruding forward to the level of the zygomatic arches. The under-chin area is cut inward. Positioned so that the plane of the two joined sections is perpendicular to the ground, the face tilts slightly forward, the forehead is in front, and the chin is regressed toward the neck. In this orientation, the eyes appear to be downcast. There is a sharp cessation of the design at the back of the front section. Above the forehead is an ornament, a crown or ornamental band. It is decorated with a pattern of pinnate-shaped sections or rays in two levels. It emerges above a narrow fringe of hair, which is divided in the center and rendered by closely spaced vertical striations. The volute-shaped ears are high on the head, nearly parallel to the back plane, but so close to the head ornament that they seem to be attached to it. The mass of the hair is dressed in beaded tresses, like cornrows, which run in a rostrocaudal direction, the rows separated by closely engraved lines intersected by even more finely engraved ones.

The eye cavities are empty and flat, and likely once held inlays. The eye sockets are carved with an elongated sinuous opening, the outer canthus of each eye higher than the inner canthus. The eyes extend from the frontal plane around to the sides, so that in side view the eyes look hooded. The nose is indented at the bridge, with the line of the nose inclined at a modest angle away from the face. The corners of the mouth abut the inside curves of the cheeks, and both lips are pulled tightly upward (the upper overhanging the lower): this makes the mouth into a full smile. Since the mouth is recessed from the main facial plane, the effect of a prominent chin is increased, which also emphasizes the smile.

Tool marks or polishing abrasions are evident on the inner surfaces of both halves and just behind the ears on the face. The two sections fit together perfectly. There is no evidence of an adhesive.

Discussion

The lack of a suspension perforation, the high polish of front and back sides, and the sharp cessation of the hair at the circumference suggest that the two sections, 76.AO.85.1 and 76.AO.86, were fitted into a metal bezel, ring mount, or similar kind of setting. Light would have shone through it, and the large “drop” of amber would have glittered, marvelous to behold.

This amber has no exact parallel in style or form. It was likely unearthed in Italy and may have been made there, but the style is that of East Greece. 76.AO.86 is remarkably close to a group of terracottas put together by François Croissant, which he named H Group, Knidos(?).1 Croissant linked the group to two of his Samian subgroups, Type A1 and Type A5, hypothesizing that a foreigner (a Knidian?) produced these terracottas in a Samian atelier. In comparison to the protomes of Croissant’s H Group, 76.AO.86 has a similar facial structure—the same triangular form, eyebrow placement, wide and high arc of the brow edge, and sharp angle of the jawline, and a similarly shaped nose, recessed mouth, tucked-in lower lip, and prominent chin. 76.AO.86 has many features in common with Samian and other South Ionian works. Among them are (1) the ivory “Artemis” from the Halos deposit at Delphi;2 (2) a marble head from Miletos in Berlin (Staatliche Museen Sk 1631);3 (3) the over-life-size marble kouros from Samos now in Istanbul;4 (4) a bronze horseman from the Heraion at Samos;5 (5) a bronze statuette of a woman from Samos;6 and (6) three Samian black-figure female head kantharoi, one from Vulci and a pair from Chiusi.7 The potters of these kantharoi have exploited the open shape of the vessels, resulting in wide, heart-shaped faces, an exaggeration of the facial type of the amber, the comparanda above, and another Getty head (, cat. no. 21).

Who or what is represented in this amber? The physiognomy suggests that the subject is female. Because of the material, the type of head ornament, and the bright smile, it is hypothesized here that this Head represents a divinity or a sphinx, as must the amber head-pendant of a crowned female subject in London (British Museum 57).8 The crown of 76.AO.86 is similar to the headdresses of some of the ivory and bone images of Artemis Orthia from the Spartan sanctuary,9 to the feathered crown worn by the female divinity of the Laconian Grächwil krater (Artemis? Potnia Theron?),10 and to some of the headdresses worn by many of the female heads on the handles of Laconian hydriae.11 (The relationship of these headdresses to those of Hathor and Bes in Egyptian and Phoenician art may be more than a visual similarity.)12

The crowns and smiles of the tiny female divinities (Potnia Theron, Artemis, or her Etruscan counterpart?) embellishing a number of sixth-century Etruscan (Caeretan?) gold ornaments are important comparisons for 76.AO.86, not only for the identity of the amber, but also because of the East Greek connection of the gold working.13 An earlier Greek parallel for this Head’s crown is the headdress worn by a seventh-century ivory sphinx from Perachora.14 In turn, the Perachoran ivory’s crown might be seen as a latter-day, schematic version of a Mycenaean fashion—such as those sported by the intensely smiling pair of sphinxes on an ivory lid from Mycenae, or the head ornament worn by the sphinx on an ivory from the Athenian Acropolis.15

If 76.AO.86 were mounted in a bezel, the mount may have resembled the earlier oval ring mounts (of gold, silver, or gilt silver) of a special class of seventh-century pendants, some of them scaraboids. Excavated examples include silver-mounted ambers from mid-seventh-century graves at Cumae and Veii, and a gold one from Vulci.16 Three other hypothetical options for the setting of 76.AO.86, two Etruscan and one Egyptian, are the embossed gold aedicula cradle mounts bent around three Egyptian faïence pataikos/dwarf amulets for a necklace buried in a tomb at Vulci,17 the embossed strip mount bent around a broken amber (for use as a pendant),18 and the Egyptian gold settings for royal heart amulets and heart scarabs of precious nephrite.19 However, while the silhouette of the Egyptian pendants is almost identical to that of 76.AO.86, the stones are flat on the reverse, not rounded like the amber.

Notes

- , pp. 18–34. ↩

- Delphi Museum 10414: , no. 33. This ivory head is probably Samian, as first suggested by P. Amandry, “Rapport préliminaire sur les statues chryséléphantines de Delphes,” 63 (1939): 86–119, seconded by , p. 38. ↩

- , pl. 44 ac; and . See also , pp. 35–37. ↩

- Istanbul Museum 1645 (which fits on the body of the draped kouros Samos 5235): , pls. 41–46 (the views of the Istanbul head on pl. 42, upper right, correspond most closely to 76.AO.86). ↩

- E. Buschor, Altsamische Standbilder I–V (Berlin, 1934–61), figs. 198–99; and , pp. 40–43, pl. 5. Compare the lower eyelids, which curve slightly upward in the center. ↩

- Samos, Vathy Museum B1441: , pp. 129–40, pls. 38–39. The resemblance of the statuette to the Getty Head is enhanced by the similarly empty eye sockets. Comparable also are the structure of the head, the arch of the forehead, the head width (from ear to ear), the smile and placement of the lips, and the upward tilting and general shape of the eyes, although there are differences—the nose is more prominent, and the chin more recessed—reasons why Croissant placed this bronze in his chap. 5 Phocaean(?) group. ↩

- The head kantharoi, of both male and female subjects, provide revealing parallels. For the head kantharos from Vulci (Munich, Antikensammlungen 2014), see , no. 484, pl. 56. For the Chiusi pair (Berlin, Staatliche Museen F4012–13), see ibid., nos. 482–83, pl. 57. Compare the short nose, wide smile, and elongated eyes. ↩

- , p. 73, pl. XXIII, describes the head ornament as “a stephane like the slats of a Venetian blind.” ↩

- See cat. no. 2. The ivory plaque of the Potnia Theron / Artemis from a dress pin, of mid-seventh-century B.C. date, and a bone head of the goddess, of about 600 B.C., are illustrated in , pls. 354–55. ↩

- For the Grächwil hydria, see cat. no. 2, n. 23. ↩

- For pertinent Laconian bronzes, see , passim. ↩

- See , passim. ↩

- The smile is very like that of the winged figures in the Potnia Theron schema (she stands between lions and atop confronted recumbent waterbirds) on the pair of earrings in Berlin (Antikenmuseum 30219) and the single figures from Praeneste and Cerveteri in London (British Museum, Jew. 1267–68) and in the Villa Giulia (Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia 40875, 53492). For the goldwork, see , pp. 58, 292, 300–301, nos. 144, 192–94. The plaquettes from Cerveteri are aedicula-like and are reminiscent of the Milesian votive reliefs with a standing figure in Berlin (see cat. no. 9, n. 2). For the East Greek aspects of the gold ornaments, see , especially pp. 56–66 (“Visages humains vus de face”), with critical references. ↩

- Athens, National Archaeological Museum 16519 (from the sanctuary of Hera Limenia): T. Dunbabin, ed., Perachora, vol. 2 (Oxford, 1962), p. 403 A I, pl. 171. Illustrated in , pl. 411. ↩

- Athens, National Archaeological Museum 7634. The box lid is from the House of the Sphinxes, Mycenae: see , no. 138, pl. 12; and , pl. 332. For the crown of the Mycenaean ivory sphinx from the Athenian Acropolis, see , no. 493, pl. 53; and , p. 229, pl. 341. ↩

- , pp. 48–49. In addition to the examples in London (British Museum 12–15: ibid., pl. III), there are many others in collections both old (New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art) and new (the Getty Museum). There is the remote possibility that the mounting may have been of amber, on the basis of one known parallel: one of the possibly male heads (686/1) from the Novi Pazar, St. Peter’s church, find was originally set into an oval amber frame, which is now lost but known from photographs. There is a notch cut above the right ear, but no perforations. As an argument against this idea, the back of the Getty pendant is rounded and polished, while the Novi Pazar example has a flat back and appears to be more roughly finished: see , pp. 129, 131, fig. 57, no. 41 (with earlier bibl.). ↩

- M. Cristofani in , pp. 134, 279, no. 93 (dated to the second quarter of the seventh century B.C.). One of the faïence figures is missing; one was given a gold perizoma. The mounts are stamped with lions, sphinxes, and monkeys. ↩

- The gold mount of the broken amber pendant are embossed with a meander and a rosette (D.C.A. collection, Geneva, Switzerland): Art of the Italic Peoples, exh. cat. (Geneva and Naples, 1993), p. 178, no. 80. ↩

- Compare, for example, the Eighteenth Dynasty heart amulet, “Royal Wife, Manhata,” in New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art 26.8.144, Fletcher Fund, 1926): , p. 215, no. 137. ↩

Bibliography

- Bulté 1991

- Bulté, J. Talismans égyptiens d’heureuse maternité: “Faïence” bleu vert à pois foncés. Paris, 1991.

- Cristofani and Martelli 1983

- Cristofani, M., and M. Martelli, eds. L’oro degli Etruschi. Novara, 1983.

- Croissant 1983

- Croissant, F. Les protomés féminines archaïques: Recherches sur les représentations du visage dans la plastique grecque de 550 à 480 av. J.-C. 2 vols. Paris, 1983.

- Freyer-Schauenburg 1974

- Freyer-Schauenburg, B. Bildwerke der archaischen Zeit und des strengen Stils: Samos. Vol. 11. Bonn, 1974.

- Hampe and Simon 1981

- Hampe, R., and E. Simon. The Birth of Greek Art: From the Mycenaean to the Archaic Period. London, 1981.

- Karakasi 2003

- Karakasi, K. Archaic Korai. Los Angeles, 2003.

- Laffineur 1978

- Laffineur, R. L’orfèvrerie rhodienne orientalisante. Athens, 1978.

- Lapatin 2001

- Lapatin, K. D. S. Chryselephantine Statuary in the Ancient Mediterranean World. New York, 2001.

- Palavestra and Krstić 2006

- Palavestra, A., and V. Krstić. The Magic of Amber. Belgrade, 2006.

- Poursat 1977

- Poursat, J. C. Catalogue des ivoires mycéniens du Musée National d’Athènes: Les ivoires mycéniens. Athens, 1977.

- Hatshepsut 2005

- Roehrig, C. H., ed. Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharaoh. With R. Dreyfus and C. A. Keller. New York, 2005.

- Stibbe 2000

- Stibbe, C. The Sons of Hephaistos. Rome, 2000.

- Strong 1966

- Strong, D. E. Catalogue of the Carved Amber in the Department of the Greek and Roman Antiquities. London, 1966.

- Walter-Karydi 1973

- Walter-Karydi, E. Samische Gefässe des 6. Jahrhunderts v. Chr. Landschaftsstile ostgriechischer Gefässe. Vol. 6.1, Samos. Bonn, 1973.