Ancient Literary Sources on the Origins of Amber

Where did amber come from? Attempts to answer this question, from the early Greek poets to Late Antique authors, were made in a wide variety of disciplines—philosophy, poetry, history, natural science, and even pharmacology. But the most important, and the most varied, answers came from perspectives that were scientific (amber comes from tree sap or lake mud or the sea), geographical (amber comes from the Northern Ocean, Liguria, or Ethiopia), or mythological (it comes from the tears of Phaethon or of Meleager’s sisters). However diverse the various origin stories, they explain amber either as being related to the sun or the planets, or as being “of water” or “of earth.” These different beliefs about amber’s origin appear to have affected the very ways it was used.

Pliny’s chapters on amber in his encyclopedic Natural History are the most extensive surviving ancient source. Compiling his work at a time when amber was beginning to flood into Rome, he provides a survey of the stories then in circulation about the formation of amber, its geographical and mythical origins, and the way it was classified and used. The depth and complexity of the information available to Pliny is striking. Evidently there was a varied and lively debate about what amber was and where it came from by the time he was writing, right down to the question of whether it was a vegetable, mineral, or faunal product. Throughout Book 37, Pliny comments critically on his source material, contrasting its validity with current evidence. He passes over accounts that range from the theory that amber was moisture from the sun’s rays to the hypothesis that it was produced by heated lake mud before offering his own scientific conclusion: amber is formed from the sap of a species of pine, and, hardened by either frost, heat, or the sea, it “is washed up on the shores of the mainland, being swept along so easily that it seems to hover in the water without settling on the sea bed.”

In many of these accounts (including Pliny’s own), the sea and rivers play an important role in the manufacture of amber. This is probably due in part to the preponderance of amber found washed up onshore, and the idea may have been fortified by a belief, prevalent in early northern solar cults, that the sun (another commonly recurring theme in amber-origin theories) passes through the waters of the earth on its nocturnal path. And then as now, sea-origin amber is often encrusted with shells (figure 22).

Figure 22

Figure 22But where, geographically, did amber come from? Pliny’s sources do not agree. Italy, Scythia, Numidia, Ethiopia, Syria, and “the lands beyond India” are among the suggestions. Pliny himself prefers those accounts that place amber’s origins in northern Europe: “It is well established,” he writes, “that amber is a product of islands in the Northern Ocean.” Herodotus is less sure: “I do not believe that there is a river called by foreigners Eridanus issuing into the northern sea, whence our amber is said to come, nor have I any knowledge of Tin-islands.… This only we know, that our tin and amber come from the most distant parts.”83

The Eridanus River to which Herodotus refers was originally a mythical river that came to be associated with the Po and sometimes with the Rhône, among others. In the ancient sources, the Eridanus migrates about the map. Pliny’s comment on his sources’ confusion about its location is typically pointed: “Such statements only make it easier to pardon their ignorance of amber when their ignorance of geography is so great.” The most likely explanation of this confusion is that the Eridanus at some point became connected in myth to memories of an early land–riverine amber route running from the Baltic to northern Italy.

Herodotus himself affirms the existence of an exchange route running from the far north all the way to the Aegean. In his discussion of the Hyperboreans (a legendary race from the far north who worshipped Apollo), he mentions “offerings wrapt in wheat straw” that they bring to Scythia and that are passed from nation to nation until they reach Delos (Apollo’s birthplace).84 You cannot reach Hyberborea by either land or sea, says Pindar (Pythian 10.29); most stories of travel to and from this region involve flight. There is something otherworldly as well as northerly about the Hyperboreans’ land.85 Scholars are undecided as to whether the offerings Herodotus mentions were actually amber, but it is likely that amber was transported on such a route.

Furthermore, Apollonius of Rhodes (whose answer to the question “Where does amber come from?” is a mythological one) provides a link between amber and the cult of Apollo in his Argonautica. He refers to a Celtic myth that drops of amber were tears shed by Apollo for the death of his son Asclepius when he visited the Hyperboreans.86 That amber should come to be associated with Apollo is not surprising, given its connections with the sun, but it is significant that the connection should occur specifically in the context of the mourning of Asclepius. Amber’s role in mourning, evidenced by its funerary use, is constantly emphasized in mythology. There is an explicit connection between this mythology and the funerary use of amber in Quintus’s Fall of Troy. At the lavish funerals of Achilles and Ajax, the mourners heaped drops of amber on the bodies. For Achilles,

Wailing captive women brought uncounted fabrics

From storage chests and threw them upon the pyre

Heaping gold and amber with them.

For Ajax,

Lucent amber-drops they laid thereon

Tears, say they, which the Daughters of the Sun,

The Lord of Omens, shed for Phaethon slain,

When by Eridanus’ flood they mourned for him.

These for undying honour to his son,

The God made amber, precious in men’s eyes.

Even this the Argives on the broad-based pyre

Cast freely, honouring the mighty dead.87

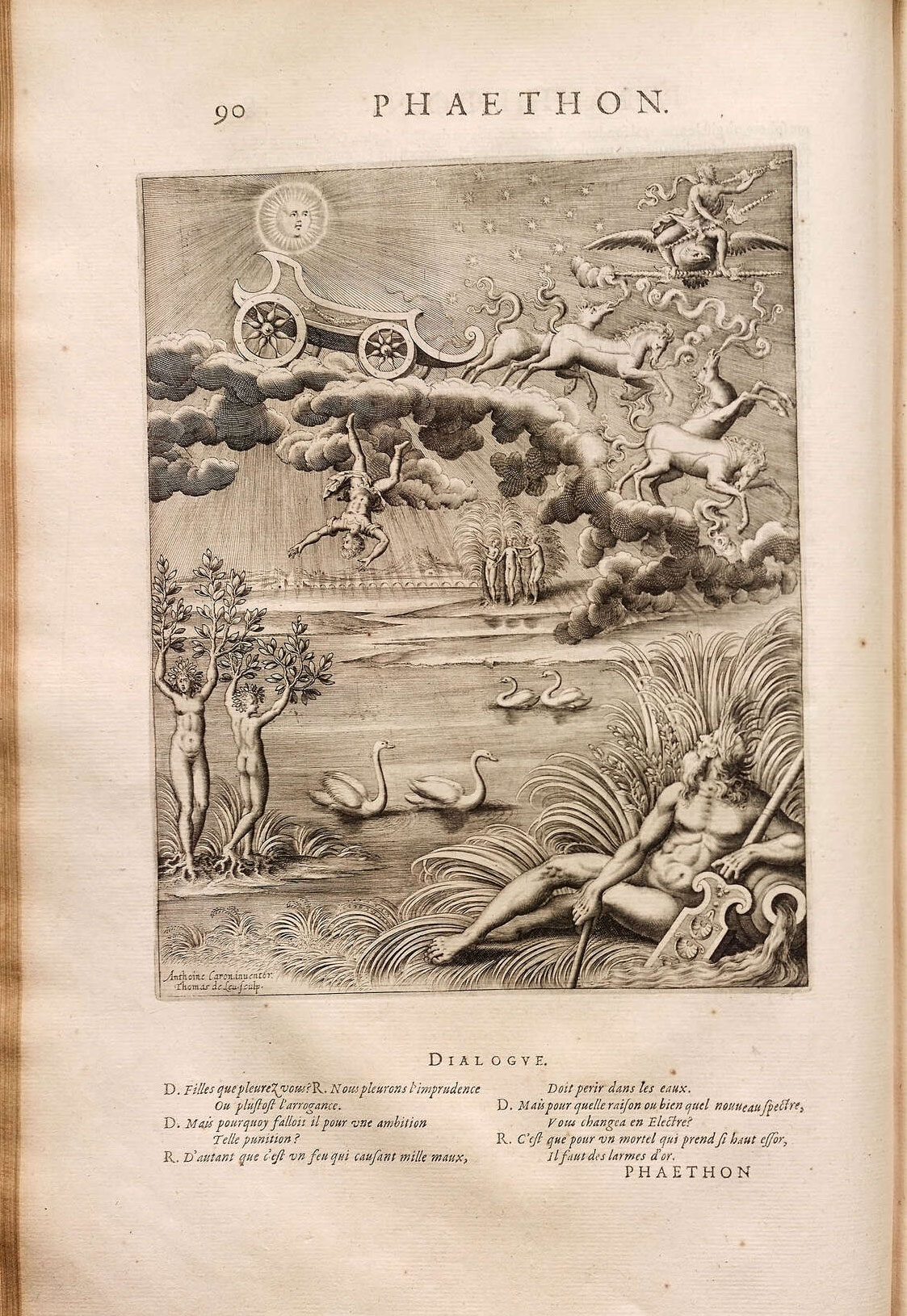

By Quintus’s time, the tale of Phaethon88 had long been the preeminent myth associated with amber.89 The name Phaethon, meaning “the shining one” or “the radiant one,” derives from the Greek verb phaethô, “to shine.” The Phaethon story, which provides a classic example of hubris followed by nemesis, was first recorded by Hesiod, and dramatized in Euripides’ mid-fifth-century Phaethon, but it might be best known today from Ovid’s version in the Metamorphoses.90

According to Ovid, Phaethon was the son of Clymene and the sun-god Helios. As an adolescent, he doubted his parentage and voyaged to the East to question his father. There the god welcomed his son and promised as proof of his paternity to grant any boon Phaethon might ask. The youth rashly demanded permission to drive the sun chariot through the sky for one day. So unsuccessful and dangerous was the young charioteer that Zeus was forced to kill Phaethon with a thunderbolt to save the world from destruction. The result was a disastrous cosmic fire. The youth’s flaming body fell into the legendary Eridanus River. His sisters, called the Heliades (daughters of Helios), stood on the riverbanks weeping ceaselessly for their brother until finally they were changed into poplars (figure 23). Thereafter the tears of the Heliades fell as drops of precious amber onto the sandy banks, to be washed into the river and eventually borne off on the waters to one day “adorn young wives in Rome.” Phaethon’s friend Cygnus, the king of Liguria, was so distressed that he left his people to mourn among the poplars and was eventually transformed himself, into a swan.

Figure 23

Figure 23Like the Celtic myth about Apollo mourning Asclepius, Phaethon’s tale is one of a young life tragically cut short. When Diodorus Siculus tells the Phaethon story in his Library of History, he ends by pointing out that amber “is commonly used in connection with the mourning attending the death of the young.”91 But as well as reminding us of amber’s role in mourning, the poplars dropping tears into the river are evidence that there were theories connecting amber to tree resin as early as the fifth century (which marks the first extant occurrence of the Phaethon myth). The link between resin drops and tears is a natural one; myrrh, for instance, is explained in myth as the tears of Myrrha, who was changed into a tree for her crimes—indeed, the Greek word for tear, dakruon, can also mean “sap” or “gum.”

A broader trend in mythology (in many cultures besides the Greco-Roman) connects precious stones generally to tears, and mythological accounts of amber’s origin do not always involve trees. Pliny refers to a (now lost) play by Sophocles that links amber to Meleager, the famous hero of the Calydonian boar hunt.92 According to one version of the myth, Meleager’s sisters, who were changed into birds (meleagrides, perhaps guinea fowl) by Artemis when he died, migrated yearly from Greece to the lands beyond India and wept tears of amber for their brother. Artemis’s role is a critical one in this story, considering the number of amber carvings that might be associated with her. While one Late Antique author places the Meleagrides on the island of Leros, opposite Miletos, Strabo sets the transformed birds at the mouth of the Po or south of Istria—locations of great interest, considering the number of seventh-century ambers in the form of birds excavated from sanctuaries and graves in both Greece and Italy.

Another amber-origin story, recounted by Pseudo-Aristotle in On Marvellous Things Heard, offers an intriguing hint of connections among amber, sun myths, and metalworking, and of the presence of figured amber and Greek artists at the mouth of the Po.93 Ever present in these accounts is the sadness of a youth’s early death, and this version involves Icarus, who was burned by flying too close to the sun. According to Pseudo-Aristotle, Icarus’s father, the master craftsman Daidalos, visited the Elektrides (“amber islands”), which were formed by the silting-up of the Eridanus River, in the gulf of the Adriatic. There he came upon the hot, fetid lake where Phaethon fell, and where the black poplars on its banks oozed amber that the natives collected for trade with the Greeks. During his stay on these islands, Daidalos erected two statues, one of tin and one of bronze, in the likenesses of himself and of his lost son.

There are recurring themes in all these myths: the death of divine or heroic youths, the mourning of the young, the sun (which was responsible for Icarus’s death as well as Phaethon’s), and the sea. Many Greek and early Roman stories about amber place its origin in the far north, and it is likely that the earliest myths incorporated knowledge of the northern solar cults and the medicinal and magical properties of amber.

Not only was amber connected to the sun, it also came to be immortalized in the stars. It was characteristic of all precious stones in antiquity to have a planetary or celestial association, and by the third century B.C. at least, the Eridanus was thought to have been transformed into a constellation, the eponymic Eridanus, or River. Late Antique sources recount how Phaethon became the constellation Auriga, the Heliades became the Hyades, and the Ligurian king became the Swan.94 In Late Antiquity, Claudian described the river god Eridanus in a manner no doubt long imagined: “On his dripping forehead gleamed the golden horns that cast their brilliance along the banks … and amber dripped from his hair.”95 Why, as Frederick Ahl asks, is the Swan a friend of the sun’s child? The answer to this question explains in part why amber was important in ancient Italy, and why the long-necked birds are represented early and often in the “solar” material. The swan was a cult bird in northern Europe during the height of Celtic power, in the Urnfield and Hallstatt phases of European prehistory. “The evidence strongly suggests that this bird was especially associated with the solar cults that were widespread in Europe, and that can be traced from the Bronze Age, into the Iron Age.”96

The constellation of Eridanus “wets the clear southern skin in its tortuous course and with starry stream flows beneath Orion’s dread sword”: so writes Claudian in his panegyric of A.D. 404. Here, too, amber’s place in Greek myths suggests that it was viewed as an ancient material, something belonging to a great age of the distant past. But it also had a practical life outside myth—by Pliny’s time, amber was very common in Rome, and a great number of amber objects were used as jewelry, incense, pharmaceuticals, and furnishings for the dead. Nonetheless, amber’s mythological significance would have had a powerful effect on the way the material was seen and employed in everyday life.

Of course, as soon as one begins to delve deeper into the relationship between the myths and the reality of amber, it becomes difficult to distinguish which is which. Myths about amber’s role in the mourning of the dead and the actual funerary use of amber, for instance, both have a direct correlation to the fact that amber can sometimes act as a tomb itself.

The connection among amber, tombs, and funerary customs is brought out in a unique Etruscan amber, the bow of a fibula, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the so-called Morgan Amber, possibly the most beautiful of all surviving pre-Roman carved amber objects (figure 24).97 The bow is carved into a complex grouping: a draped and shod female wearing a pointed hat holds the base of a small vase in her right hand and touches it with her left. A young, beardless man, with flowing hair, long garment, and bare feet, supports himself on his left arm. Nestled between them is a long-necked bird, presumably a swan. At the foot of the couch is an attendant. The amber apparently depicts a ceremonial banquet, but is the couple mortal or divine? Are the figures Aphrodite and Adonis (Etruscan: Turan and Atunis) and the bird the goddess’s swan? Or is this an elite couple? If so, is the swan a symbol or a part of the event? The iconography of the reclining couple and the ceremonial banquet had spread earlier from the Ancient Near East to Greece and Etruria. Significant Archaic Etruscan sculpted and painted depictions are extant. If this is a funerary object and the subjects divine, rich mythological implications are possible. If the subjects are mortal, the pin could have functioned in some manner as a “substitution” for the deceased.

Figure 24

Figure 24As Jean-René Jannot writes about the Etruscan-depicted dead:

Was [a wall painting, an effigy sarcophagus] considered the physical envelope for that which does not die, the hinthial [soul, or shade]? None of these monuments were made to be seen.… Was the deceased, through his material image, believed to be living in the funerary chamber, which has become a house, or in the trench where offerings of food were set out for him?98

Certainly, inclusions in amber—life visibly preserved for eternity—would not have been ignored when preparing amber for funerary purposes.

The insects and flora in amber, which Aristotle and later Pliny and Tacitus point to as proof of amber’s origin as earth-born, as tree resin,99 are apt metaphors for entombment and for the ultimate functions of the funeral ritual: to honor the deceased with precious gifts and to make permanent the memory of their lives. Three of Martial’s epigrams are devoted to this correlation:

Shut in Phaethon’s drop, a bee both hides and shines, so that she seems imprisoned in her own nectar. She has a worthy reward for all her sufferings. One might believe that she herself willed so to die.

As an ant was wandering in Phaethonic shade, a drop of amber enfolded the tiny creature. So that she was despised but lately, while life remained, and now has been made precious by her death.

While a viper crawled along the weeping branches of the Heliads, a drop of amber flowed onto the creature in its path. As it marveled to find itself stuck fast in the viscous fluid, it stiffened, bound of a sudden by congealed ice. Be not proud, Cleopatra, of your royal sepulchre, if a viper lies in a nobler tomb.100

It is very unlikely that a swift, small snake could be entombed in such a fashion, but it is also only fair to allow Martial a degree of poetic license, given Cleopatra’s traditional association with the asp. A more intriguing possibility remains, however: that Martial was describing something he had actually seen or heard about—an early instance of amber forgery.101

Notes

- Herodotus, Histories 3.115.↩

- Ibid. 4.32–36. See J. Bouzek, “Xoana,” Oxford Journal of Archaeology 19, no. 1 (2000): 111; J. Bouzek, Greece, Anatolia and Europe: Cultural Interrelations during the Early Iron Age (Jonsered, Sweden, 1997), pp. 35–38; , pp. 41–45, with reference to J. Tréheux, “La réalité historique des offrandes hyperboréennes de Délos,” in Studies Presented to D. M. Robinson (St. Louis, 1953), pp. 758–59; and F. M. Ahl, “Amber, Avallon, and Apollo’s Singing Swan,” American Journal of Philology 103 (1982): 373–411. , p. 260, points to C. W. Beck, G. C. Southard, and A. A. Adams, “Analysis and Provenience of Minoan and Mycenaean Amber, II. Tiryns,” Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 9 (1968): 5–19, and the connection of the “Tiryns” type of gold and amber beads to the offerings. See also , pp. 110–11. Callimachus (Hymn 4.283–84) differs in this, believing that the offerings are wheat. On this, see C. T. Seltman, “The Offerings of the Hyperboreans,” Classical Quarterly 22 (1928): 155–59.↩

- Ahl 1982 (n. 84, above), p. 378.↩

- Apollonius, Argonautica 4.611–18.↩

- For the passage about the funeral of Achilles (The Fall of Troy 3.683–85), see Quintus of Smyrna, The Trojan Epic: Posthomerica, trans. and ed. A. James (Baltimore, 2006). For the funeral of Ajax (The Fall of Troy 5.625–30), the translation is by A. S. Way (see n. 73, above).↩

- This Phaethon is not the only Phaethon of Greek myth; see, for example, J. Diggle, Euripides’ Phaethon (Cambridge, 1970).↩

- Pliny, Natural History 37.11.↩

- Ovid, Metamorphoses 1.750–2.380. See the extensive discussion of Euripides’ Hippolytus and Phaethon in Diggle 1970 (n. 88, above).↩

- Diodorus Siculus, Library of History 5.23–24.↩

- The story may have had particular relevance in Italy (especially in Etruria), a land famous for its fierce boars.↩

- On Marvellous Things Heard 81–82. A. Spekke, The Ancient Amber Routes and the Geographical Discovery of the Eastern Baltic (Chicago, 1957), appears to have been the first to draw attention to this story in relation to amber. See also Grilli 1975 (in n. 52, above); ; and , pp. 32–34.↩

- See , pp. 16–22; ; and for further discussion of the planetary and celestial aspects of Phaethon.↩

- Claudian, vol. 2, “Panegyric on the Sixth Consulship of the Emperor Honorius,” trans. M. Platnauer, Loeb Classical Library 136 (Cambridge, MA, 1922). Four amber pendants from Italy, each in the form of a bull-bodied man, may represent this river god.↩

- A. Ross, Pagan Celtic Britain: Studies in Iconography and Tradition (London, 1967), p. 234, quoted in Ahl 1982 (n. 84, above), p. 390.↩

- Metropolitan Museum of Art 17.190.2067, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917: , pp. 284–85, 471, no. 326; , p. 31, figs. 97–98; ; and . Richter cites two other ambers with similar subjects, a fragmentary work in the Metropolitan Museum (23.160.96) and an example once in the Stroganoff Collection (, vol. 1, p. 78, pl. XLVII.1).↩

- , p. 58.↩

- Aristotle, Meteorology 4.10; Pliny specifies ants, gnats, and lizards, the first two signifying similar-appearing and excellent specimens of amber; Tacitus, Germania 45.↩

- Martial, Epigrams 4.32, 4.59, 6.15, in vol. 2, ed. and trans. D. R. S. Bailey, Loeb Classical Library 95 (London and Cambridge, MA, 1993). See P. A. Watson, “Martial’s Snake in Amber: Ekphrasis or Poetic Fantasy?,” Latomus 61 (2001): 938–43. Was this snake in amber a forgery?↩

- See , pp. 6–9 (“fake amber”); , pp. 133–41 (“processed amber, imitations, and forgeries”); D. Grimaldi, A. Shedrinsky, A. Ross, and N. S. Baer, “Forgeries of Fossils in ‘Amber’: History, Identification, and Case Studies,” Curator 37 (1994): 251–74; and A. M. Shedrinsky, D. A. Grimaldi, J. J. Boon, and N. S. Baer, “Application of Pyrolysis Gas Chromatography and Pyrolysis Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry to the Unmasking of Amber Forgeries,” Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 25 (1993): 77–95.↩

Bibliography

- Albizzatti 1919

- Albizzatti, C. “Un’ ambra scolpita d’arte ionica nella raccolta Morgan.” Rassegna d’arte antica e moderna 10 (1919): 183–200.

- Dopp 1997

- Dopp, S. “Die Tränen von Phaethons Schwestern wurden zu Bernstein: Der Phaethon-Mythos in Ovid’s ‘Metamorphosen.’” In Bernstein: Tränen der Götter, edited by M. Ganzelewski and R. Slotta, pp. 1–10. Exh. cat. Bochum, 1996.

- Fuscagni 1982

- Fuscagni, S. “Il pianto ambrato delle Eliadi, l’Eridano e la nuova stazione preistorica di Frattesina Polesine.” Quaderni urbanati di cultura classica 12 (1982): 101–13.

- Geerlings 1996

- Geerlings, W. “Die Tränen der Schwestern des Phaethon-Bernstein im Altertum.” In Bernstein: Tränen der Götter, edited by M. Ganzelewski and R. Slotta, pp. 395–400. Exh. cat. Bochum, 1996.

- Grimaldi 1996

- Grimaldi, D. A. Amber: Window to the Past. New York, 1996.

- Hughes-Brock 1985

- Hughes-Brock, H. “Amber and the Mycenaeans.” Journal of Baltic Studies 16, no. 3 (1985): 257–67.

- Jannot 2005

- Jannot, J.-R. Religion in Ancient Etruria. Translated by J. Whitehead. Madison, WI, 2005.

- Kredel 1923–24

- Kredel, F. “Ein archaisches Schmuckstück aus Bernstein.” 38–39 (1923–24): 169–80.

- Mastrocinque 1991

- Mastrocinque, A. L’ambra e l’Eridano: Studi sulla letteratura e sul commercio dell’ambra in età preromana. Este, 1991.

- Art of the Classical World 2007

- Picón, C. A., et al. Art of the Classical World in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, 2007.

- Pollak and Muñoz 1912

- Pollak, L., and A. Muñoz. Pièces de choix de la collection du comte Grégoire Stroganoff à Rome. 2 vols. Rome, 1912.

- Richter 1940

- Richter, G. M. A. Handbook of the Etruscan Collection. Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, 1940.

- Ross 1998

- Ross, A. Amber: The Natural Time Capsule. London, 1998.