The Properties of Amber

Amber is a light material, with a specific gravity ranging from 1.04 to 1.10, only slightly heavier than that of water (1.00). Amber may be transparent or cloudy, depending on the presence and number of air bubbles (figure 13). It frequently contains large numbers of microscopic air bubbles, allowing it to float and to be easily carried by rivers or the sea. White opaque Baltic amber may contain as many as 900,000 minuscule air bubbles per square millimeter and floats in fresh water. Clear Baltic amber sinks in fresh water but is buoyant in saltwater. Baltic amber has some distinguishing characteristics rarely found in other types of amber: it commonly contains tiny hairs that probably came from the male flowers of oak trees, and tiny pyrite crystals often fill cracks and inclusions. Another feature found in Baltic amber is the white coating partly surrounding some insect inclusions, formed from liquids that escaped from the decaying insects.40

Figure 13

Figure 13Amber’s hardness varies from 2 to 3 on the Mohs scale (talc is 1 and diamond 10). This relative softness means that amber is easily worked. It has a melting-point range of 200 to 380°C, but it tends to burn rather than melt. Amber is amorphous in structure and, if broken, can produce a conchoidal, or shell-like, fracture. It is a poor conductor and thus feels warm to the touch in the cold, and cool in the heat. When friction is applied, amber becomes negatively charged and attracts lightweight particles such as pieces of straw, fluff, or dried leaves. Its ability to produce static electricity has fascinated observers from the earliest times. Amber’s magnetic property gave rise to the word electricity: amber (Greek, elektron) was used in the earliest experiments on electricity.41 Amber’s natural properties inspired myth and legend and dictated its usage.

In antiquity, before the development of colorless clear glass that relies on a complex technique perfected in the Hellenistic period, the known clear materials were natural ones: water and some other liquids; ice; boiled honey and some oils; rock crystal; some precious stones; and amber.42 Transparent amber is a natural magnifier, and, when formed into a regularly curved surface and given a high polish, it can act as a lens.43 A clear piece of amber with a convex surface can concentrate the sun’s rays. One ancient source suggests that such polished ambers were used as burning lenses.

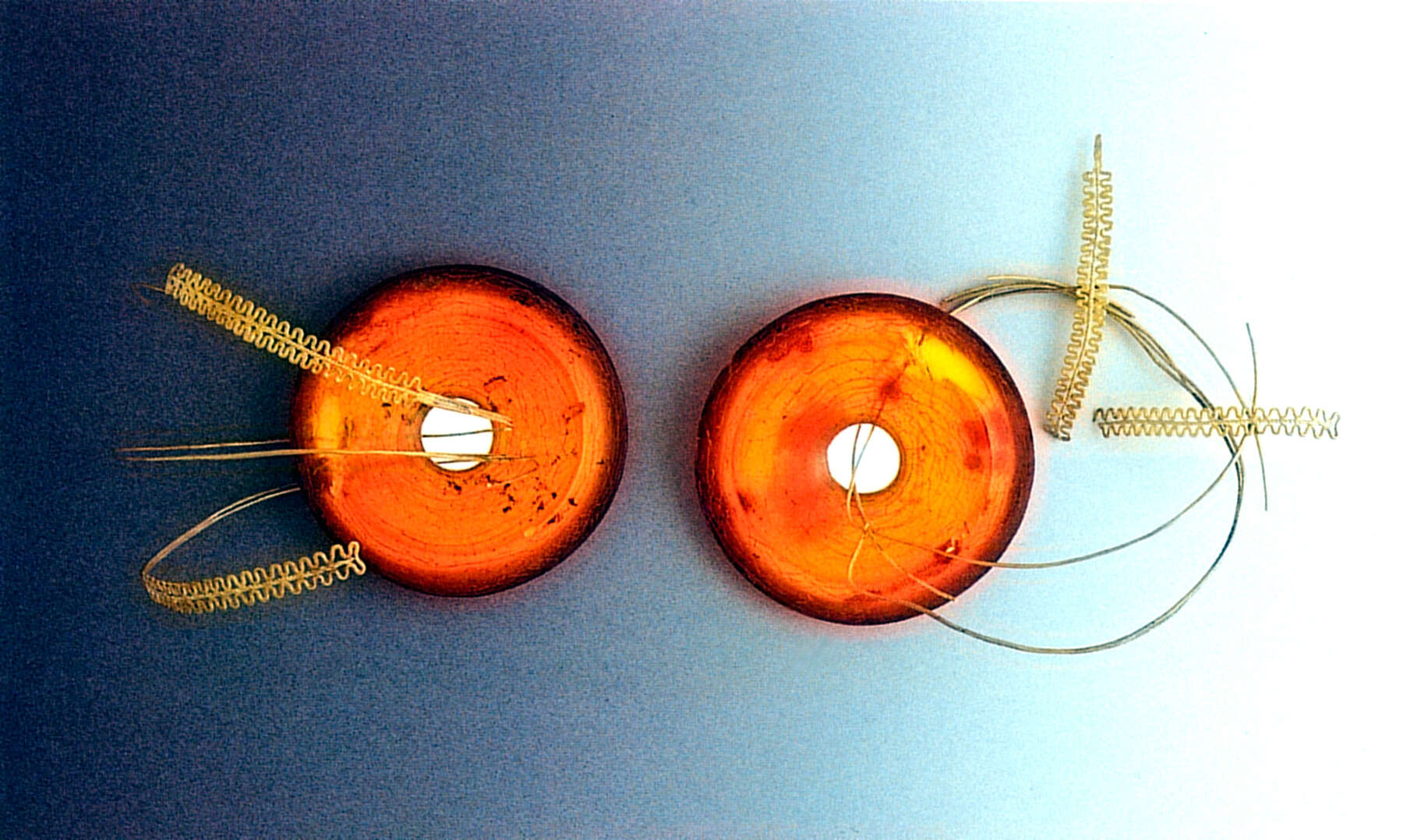

Once amber is cleaned of its outer layers and exposed to air, its appearance—its color, degree of transparency, and surface texture—eventually will change. As a result of the action of oxygen upon the organic material, amber will darken: a clear piece will become yellow; a honey-colored piece will become red, orange-red, or red-brown, and the surface progressively will become more opaque (figure 14).44 Oxidation commences quite quickly and starts at the surface, which is why some amber may appear opaque or dark on its surface and translucent at breaks or when subjected to transmitted light. However, the progress of oxidation is variable and depends on the time of exposure and other factors, such as the amount and duration of exposure to light. In archaeologically recovered amber, the state of the material is dependent upon burial conditions, and the degree of oxidation can vary widely, as the Getty collection reveals. The breakdown of the cortex causes cracking, fissuring, flaking, chipping, and, eventually, fractures. Only a very few ancient pieces retain something of their original appearance, in each case because of the oxygen-free environment in which it was buried. For instance, two fifth-century B.C. female head pendants that were excavated at waterlogged Spina are remarkable for their clear, pale yellow color (figure 15).45 A large group of seventh-century B.C. amber-embellished objects from the cemeteries of Podere Lippi and Moroni-Semprini in Verucchio (Romagna) were preserved along with other perishable objects by the stable anaerobic conditions of the Verucchio tombs, which had been sealed with a mixture of water and clay (figure 16).46 Various colors and degrees of transparency are in evidence, from pale, clear yellow to clear orange or red to opaque yellows, oranges, reds, and tans. Inclusions are common.

Figure 14

Figure 14 Figure 15

Figure 15 Figure 16

Figure 16Many pre-Roman figured ambers exploit the material’s transparency, offering the possibility of reading through the composition: the back is visible from the front and vice versa, albeit blurrily. This is a remarkable artistic conception, iconographically powerful and magical. Two extraordinary examples are the Getty Lion (see figure 54) and the British Museum Satyr and Maenad (figure 17).47 From its top, the underside of the lion can be discerned. In the multigroup composition of the London amber, the large snake on the reverse appears to join in reveling with the figures on the front.

Figure 17

Figure 17A number of seventh-century Greek, Etruscan, and Campanian objects include amber set into precious metal mounts or backed with silver or gold foil.48 Some are internally lit by foil (or possibly tin) tubes. Amber’s glow, its brilliance and shine, would be immeasurably enhanced in this way.49 Simply shaped amber pieces set into gold and silver are mirrorlike, emanating radiance and banishing darkness.50 Amber faces once mounted on polished metal, the Getty Heads of a Female Divinity or Sphinx (figures 18 and 45) might even seem to issue light, like the principal astral bodies, or to capture the shimmer of light on water.51

Figure 18

Figure 18Notes

- , p. 11.↩

For the basic properties of amber, see , p. 4. The word electricity was coined by W. Gilbert, a physician at the court of Queen Elizabeth I, to describe this property in his 1600 book On the Magnet, Magnetic Bodies and That Great Magnet the Earth.

The early Greek philosopher Thales of Miletos is credited by Diogenes Laertius as the first to recognize amber’s magnetism: “Arguing from the magnet and from amber, he attributed a soul or life even to inanimate objects” (Diogenes Laertius 1.24, vol. 1, ed. and trans. R. D. Hicks, Loeb Classical Library 184 [London, 1993]). E. R. Caley and J. C. Richards, Theophrastus on Stones (Columbus, 1956), p. 117, argue that this claim rests on shaky ground; that Thales was the first to mention the property can be inferred only indirectly from Diogenes Laertius’s statement: “Aristotle and Hippias say that, judging by the behaviour of the lodestone and amber, he also attributed souls to lifeless things.” Caley and Richards consider the possibility “that it was Hippias who said that Thales understood the attractive property of amber, but there is no way of confirming such an inference because the works of Hippias are not extant.” Plato (Timaeus 80c) alludes to amber’s magnetism but denies that it is a real power of attraction. Aristotle does not mention amber in the relevant section of On the Soul (De Anima 1.2.405A). Thus, following Caley and Richards, Theophrastus is the earliest extant account. If Thales did describe amber’s static electricity, he may have done so based on his observation of wool production, which used amber implements: distaff, spindle, and whorls. I owe this observation to , who calls attention not only to the famous wool of Miletos, but also to the number of extant seventh-century spinning tools. Pliny notes that Syrian women used amber whorls in weaving and that amber picks up the “fringes of garments,” and also comments on amber’s electrostatic property. But, unlike Plato, he thinks its magnetic property is like that of iron. Plutarch (Platonic Questions 7.7) explains that “the hot exhalation released by rubbing amber acts in the same ways as the emanations from the magnet. That is, it displaces air, forming a vacuum in front of the attracted object and driving air to the rear of it”: De Lapidibus, ed. and trans. D. E. Eichholz (Oxford, 1965), p. 200, n.b.↩

- Clear colorless glass (with antimony used as the decolorizing agent) is documented in the eighth century B.C. in western Asia and again in the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. in Greece. In Egypt, the use of manganese as a decolorizing agent became common in the first century B.C.; see E. M. Stern and B. Schlick-Nolte, Early Glass of the Ancient World, 1600 B.C.–A.D. 50: Ernesto Wolf Collection (Ostfildern, Germany, 1994), p. 20.↩

For an excellent overview of lenses and their ancient employment, see , pp. 39–41, 110; and , pp. 451–64. According to , p. 41, “The discovery of crystals that could have served as magnifying lenses has been reported from Bronze Age sites, and although no similar objects can be dated to the Hellenistic period, some exist from Roman contexts.” He also points out that “developments in optics already in the Classical period suggest the possibility of magnifying lenses.” Various ancient authors describe the magnification of objects: Aristotle (Posterior Analytics 1.31) and Theophrastus (On Fire 73) observe “that convex pieces of glass can concentrate the sunrays, and light fire … and an earlier reference in Aristophanes (Clouds 766–75) indicates how well observed [this] was.” “For a lens to be able to contract light, a piece of glass with [a] regularly curved surface and a minimum diameter of around four centimeters was needed. Such a lens will have a short focus (between six and nine millimeters) and will therefore be quite useless as a general eye aid, but quite appropriate for a magnifying glass” (ibid.). Although no ancient literary source mentions amber’s natural magnifying property, it is difficult to imagine that it went unnoticed. Many bulla-shaped amber pendants (of as early as seventh-century date) have regularly curved surfaces and are the right size to use as magnifiers, especially if the resin were clear. (On amber bullae, see n. 152.) The various techniques necessary to make a clear magnifying or burning lens from amber apparently were available by the first century A.D. The carving and polishing tools and technology were age-old, and as for the clarification process, Pliny relates a technique for “dressing” amber by boiling it in the fat of a suckling pig, a necessary step in making imitation transparent gemstones from amber, which Pliny also describes. A section of an entry (Hualê) in the Byzantine Suda may not refer to a glass lens, but rather to an amber one: “[A glass] is a round-shaped device of amber glass, contrived for the following purpose: when they have soaked it in oil and heated it in the sun they introduce a wick and kindle [fire]. So the old man is saying, in conversation with Socrates: if I were to start a fire with the amber and introduce fire to the tablet of the letter, I could make the letters of the lawsuit disappear.” See “Ὑάλη,” trans. David Whitehead, March 19, 2006, Suda On Line, www.stoa.org/sol-entries/upsilon/6 (accessed November 27, 2009).

Processed (boiled, molded, and then ground) amber lenses are described by the end of the seventeenth century. In 1691, C. Porshin of Königsberg invented an amber burning glass, which was said to be better than the glass kind; he also used amber to make spectacles. See O. Faber, L. B. Frandsen, and M. Ploug, Amber (Copenhagen, 2000), p. 101. For illustrations of amber lenses of the early modern period, see .↩

- See , pp. 18–19; and , p. 14 (with reference to M. Bauer, Precious Stones [London, 1904], p. 537).↩

- Ferrara, Museo Archeologico Nazionale 44877–78, from Tomb 740 B at Spina: C. C. Cassai, “Ornamenti femminile nelle tombe di Spina,” in , pp. 42–47; Spina: Storia di una città tra greci e etruschi, exh. cat. (Ferrara, 1993); and , fig. 470.↩

- For splendid photographs of the Verucchio material, see .↩

- , pp. 61–62, pl. XV.↩

- See , p. 41, on the importance of color to ancient gemologists; he remarks that the “contrast of the translucent stone against the golden background of the ring was thought to be a merit of the jewel.” “A gold tube lining the perforation of a transparent or translucent material such as amber or rock crystal has a marked effect on the brightness and thus appearance of the bead and is, in effect, a form of foiling”: J. Ogden, “The Jewelry of Dark Age Greece: Construction and Cultural Connections,” in The Art of the Greek Goldsmith, ed. D. Williams (London, 1998), pp. 16–17, also nn. 19–21 (in reference to objects from Lefkandi, the Tomb 2 jewelry from Tekke, the Elgin group, and an eighth-century tomb from Salamis).↩

- Agalma is a Greek word used to describe the quality of brilliance; it is perhaps related etymologically to aglaos (shining). See , p. 65. On agalma and agalmata, see n. 6.↩

The three gold pendants inlaid with amber from the Regolini-Galassi Tomb are superb examples of this mirrorlike quality (Vatican, Museo Gregoriano Etrusco 691, from the Sorbo Necropolis, Cerveteri): , p. 262, no. 31; and L. Pareti, La tomba Regolini-Galassi del Museo gregoriano etrusco e la civiltà dell’Italia centrale nel secolo VII a.c. (Vatican City, 1947). The ivory handle of an Orientalizing ceremonial axe was inlaid with amber rectangles, circles, and triangles mounted on tinfoil, making them appear like tiny mirrors (Florence, Museo Archeologico Nazionale 70787): , p. 238, no. 268, where M. C. Bettini calls attention to the technique and notes parallels from Casale Marittimo and Verucchio.

How an amber “mirror,” however tiny, worked for the living or for the dead is worth reflection. That all documented mirrors from Etruria, and most from the rest of the circum-Mediterranean, come from graves (many with evidence of use wear) is critical to their interpretation. J. Lerner, “Horizontal-Handled Mirrors: East and West,” Metropolitan Museum Journal 31 (1996): n. 3, compares the ancient disk mirror-fibula to the large amber-decorated fibulae found in Etruscan tombs (with reference to the “Morgan Amber” in New York [see figure 24]; she acknowledges J. Mertens for the observation). On reflection and mirror symbolism, see G. Robins, “Dress, Undress, and the Representation of Fertility and Potency in New Kingdom Egyptian Art,” in , pp. 32–33; A. Stewart, “Reflections,” in , pp. 136–54; J. Neils, “Reflections of Immortality: The Myth of Jason on Etruscan Mirrors,” in , pp. 190–95; ; G. Pinch, Votive Offerings to Hathor (Oxford, 1994), pp. 235–38; A. Kozloff, “Mirror, Mirror,” Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 71, no. 8 (1984): 271–76. For mirrors in the history of art, see Source 4, nos. 2–3 (1985); L. O. K. Congdon, Caryatid Mirrors of Ancient Greece (Mainz, 1981); G. F. Hartlaub, Zauber des Spiegels: Geschichte und Bedeutung des Spiegels in der Kunst (Munich, 1951); and H. Schwarz, “The Mirror in Art,” Art Quarterly 13 (1952): 96–118. G. Robins’s comments have relevance beyond Egypt (Robins in , p. 32): “Mirrors, therefore, were not simply items in which one could see one’s reflection, but were overlaid with symbolism relating to fertility and also health, and were surely believed to protect the user in this life. However, like the fertility figurine, they usually had a funerary function, too. Many mirrors have been found in burials, and it can be deduced that their positive symbolism would also have been regarded as helping the deceased to achieve rebirth into the afterlife.” The mirror was a type of object closely equated with the disk of the sun as well as with that of the moon, but its distinctive Egyptian form is most like that of the visible sun. See n. 161 on the connection of mirrors and the sun and the possibility of drawing down the power of the sun.↩

- , p. 123. Here and in later studies, I. J. Winter describes “the quality of intense light, or radiance, emanating from a particular work” as “one of the most positive attributes in descriptions of what we would call Mesopotamian ‘art.’” She underlines that it is “the combination of light-plus-sheen yielding a kind of lustrousness” that was particularly positive, auspicious, and sacral, not only in Mesopotamia, but also in other cultures. This is borne out by many of the forms and subjects of amber and amber-enhanced objects of ancient Greece and Italy.↩

Bibliography

- Due donne 1993

- Baldoni, D., ed. Due donne dell’Italia antica: Corredi da Spina e Forentum. Exh. cat. Padua, 1993.

- Bartoloni et al. 2000

- Bartoloni, G., et al., eds. Principi etruschi: Tra Mediterraneo ed Europa. Exh. cat. Bologna, 2000.

- Cristofani and Martelli 1983

- Cristofani, M., and M. Martelli, eds. L’oro degli Etruschi. Novara, 1983.

- De Puma and Small 1994

- De Puma, R., and J. P. Small, eds. Murlo and the Etruscans: Art and Society in Ancient Etruria. Madison, WI, 1994.

- Bernstein 1996

- Ganzelewski, M., and R. Slotta, eds. Bernstein: Tränen der Götter. Exh. cat. Bochum, 1996.

- Verucchio 1994

- Il dono delle Eliadi: Ambre e oreficerie dei principi etruschi di Verucchio. Exh. cat. Rimini, 1994.

- Kampen 1996

- Kampen, N. B., ed. Sexuality in Ancient Art: Near East, Egypt, Greece, and Italy. Cambridge, 1996.

- Negroni Catacchio 1989

- Negroni Catacchio, N. “L’ambra: Produzione e commerci nell’Italia preromana.” In Italia, omnium terrarum parens: La civiltà degli Enotri, Chone, Ausoni, Sanniti, Lucani, Brettii, Sicani, Siculi, Elimi, edited by C. Ampolo et al., pp. 659–96. Milan, 1989.

- Pinch 1994

- Pinch, G. Magic in Ancient Egypt. Austin, TX, 1994.

- Plantzos 1997

- Plantzos, D. “Crystals and Lenses in the Graeco-Roman World.” 101 (1997): 451–64.

- Plantzos 1999

- Plantzos, D. Hellenistic Engraved Gems. New York, 1999.

- Ross 1998

- Ross, A. Amber: The Natural Time Capsule. London, 1998.

- Schwarzenberg 2002

- Schwarzenberg, E. “L’ambre: Du mythe à l’épigramme.” In L’épigramme de l’Antiquité au XVIIe siècle ou Du ciseau à la pointe, edited Jeanne Dion, pp. 33–67. Collection Études anciennes, 25. Nancy and Paris, 2002.

- Stewart 1997

- Stewart, A. F. Art, Desire and the Body in Ancient Greece. New York, 1997.

- Strong 1966

- Strong, D. E. Catalogue of the Carved Amber in the Department of the Greek and Roman Antiquities. London, 1966.

- Winter 1994

- Winter, I. J. “Radiance as an Aesthetic Value in the Art of Mesopotamia (with Some Indian Parallels).” In Art: The Integral Vision; A Volume of Essays in Felicitation of Kapila Vatsyayan, edited by B. N. Saraswati et al., pp. 123–31. New Delhi, 1994.