What Is Amber?

Figure 8

Figure 8It is important to say that amber is much studied but still not fully understood. The problems begin with the names by which the material is known: amber, Baltic amber, fossil resin, succinite, and resinite. Although all these terms have been used to describe the material discussed in this catalogue, they have confused as much as they have clarified. It is generally accepted that amber is derived from resin-bearing trees that once clustered in dense, now extinct forests.22 Despite decades of study, there is no definite conclusion about the botanical source of the vast deposits of Baltic amber, as Jean H. Langenheim recently summarized in her compendium on plant resins:

It is clear that the amber is not derived from the modern species of Pinus, but there are mixed signals from suggestions of either an araucarian Agathis-like or a pinaceous Pseudolarix-like resin producing tree.… Although the evidence appears to lean more toward a pinaceous source, an extinct ancestral tree is probably the only solution.23

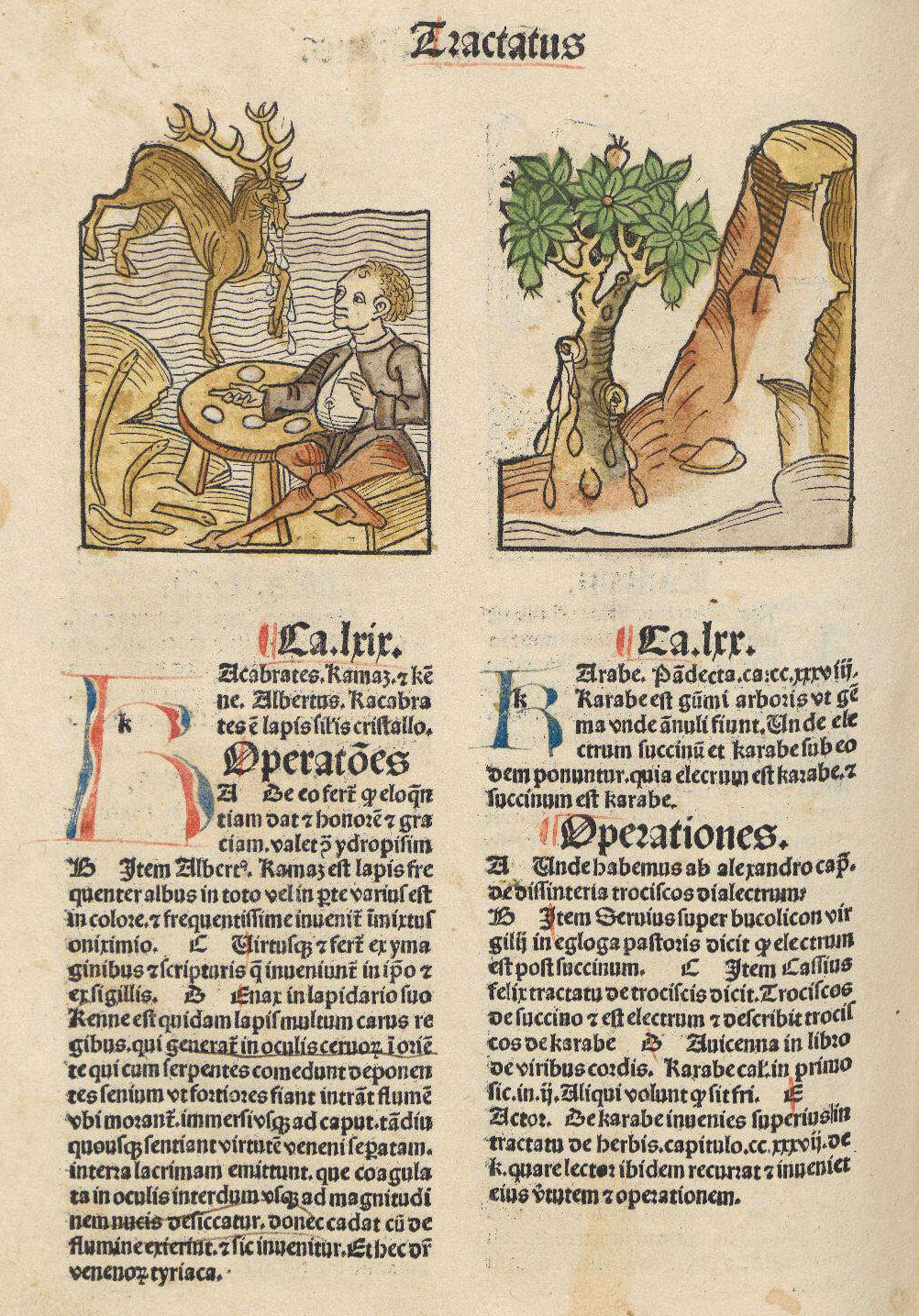

Geologically, amber has been documented throughout the world (figure 8), with most deposits found in Tertiary-period sediments dating to the Eocene, a few to the Oligocene and Miocene, and fewer still to later in the Tertiary. Amber is formed from resin exuded from tree bark (figure 9), although it is also produced in the heartwood. Resin protects trees by blocking gaps in the bark. Once resin covers a gash or break caused by chewing insects, it hardens and forms a seal. Resin’s antiseptic properties protect the tree from disease, and its stickiness can gum up the jaws of gnawing and burrowing insects.24 In the primordial “amber forest,” resin oozed down trunks and branches and formed into blobs, sheets, and stalactites, sometimes dripping onto the forest floor. On some trees, exuded resin flowed over previous flows, creating layers. The sticky substance collected detritus and soil and sometimes entrapped flying and crawling creatures (figure 10). Eventually, after the trees fell, the resin-coated logs were carried by rivers and tides to deltas in coastal regions, where they were buried over time in sedimentary deposits. Most amber did not originate in the place where it was found; often, it was deposited and found at a distance from where the resin-producing trees grew. Most known accumulations of amber are redepositions, the result of geological activity.25

Figure 9

Figure 9 Figure 10

Figure 10Chemically, the resin that became amber originally contained liquids (volatiles) such as oils, acids, and alcohols, including aromatic compounds (terpenes) that produce amber’s distinctive resinous smell.26 Over time, the liquids dissipated and evaporated from the resin, which began to harden as the organic molecules joined to form much larger ones called polymers. Under the right conditions, the hardened resin continued to polymerize and lose volatiles, eventually forming amber, an inert solid that, when completely polymerized, has no volatiles.27 Most important, the resins that became amber were buried in virtually oxygen-free sediments.

How long does it take for buried resin to become amber? The amberization process is a continuum extending from freshly hardened resins to rocklike ones, and, as David Grimaldi points out, “No single feature identifies at what age along that continuum the substance becomes amber.”28 Langenheim explains: “With increasing age, the maturity of any given resin will increase, but the rate at which it occurs depends on the prevailing geologic conditions as well as the composition of the resin.… Changes appear to be a response primarily to geothermal stress since chemical change in the resin accelerates at higher temperatures.”29

While some experts maintain that only material that is several million years old or older is sufficiently cross-linked and polymerized to be classified as amber, others opt for a date as recent as forty thousand years before the present.30 Much depends on the soil conditions of the resin’s burial. In its final form, amber is much more stable than the original substance. Amber is organic, like petrified wood or dinosaur bones, but, unlike those substances, it retains its chemical composition over time, and that is why some experts resist calling it a fossil resin (a nevertheless useful term).31 Amber can also preserve plant matter (figure 11), bacteria, fungi, worms, snails, insects, spiders, and (more rarely) small vertebrates. Some pieces of amber contain water droplets and bubbles, products of the chemical breakdown of organic matter. It is not entirely understood how resins preserve organic matter, but presumably the chemical features of amber that preserve it over millennia also preserve flora and fauna inside it.32 It must be that amber’s “amazing life-like fidelity of preservation … occurs through rapid and thorough fixation and inert dehydration as well as other natural embalming properties of the resin that are still not understood.”33 The highly complex process that results in amber formation gave rise to a wealth of speculation about its nature and origins. Whence came a substance that carried within it the flora and fauna of another place and time, one with traces of the earth and sea, one that seemed even to hold the light of the sun?

Figure 11

Figure 11Notes

- Recent sources consulted include E. Trevisani, “Che cosa è l’ambra,” in , pp. 14–17; E. Ragazzi, L’ambra, farmaco solare: Gli usi nella medicina del passato (Padua, 2005); ; ; ; ; ; ; ; Å. Dahlström and L. Brost, The Amber Book (Tucson, AZ, 1996); ; B. Kosmowska-Ceranowicz and T. Konart, Tajemnice bursztynu (Secrets of Amber) (Warsaw, 1989); ; and J. Barfod, F. Jacobs, and S. Ritzkowski, Bernstein: Schätze in Niedersachsen (Seelze, 1989). The late C. W. Beck’s lifetime of work on amber analysis is critical to any study of the material.↩

- , p. 169.↩

- , p. 2.↩

- , p. 451, with reference to , pp. 16–17.↩

- , p. 3: “The polymers are cyclic hydrocarbons called terpenes.… Amber generally consists of around 79% carbon, 10% hydrogen, and 11% oxygen, with a trace of sulphur.”↩

- , p. 3.↩

- , p. 16.↩

- , pp. 144–45.↩

- , p. 146, following .↩

- , p. 3, in describing the amberization process, points to the critical element of the kinds of sediments in which the resin was deposited: “but what is not so clear is the effect of water and sediment chemistry on the resin.” In the ancient world, amber does not seem to have been considered a fossil like other records of preserved life—petrified wood, skeletal material, and creatures in limestone. See A. Mayor, The First Fossil Hunters: Paleontology in Greek and Roman Times (Princeton, 2000).↩

- , p. 12.↩

- , p. 150.↩

Bibliography

- Anderson and Crelling 1995

- Anderson, K. B., and J. C. Crelling, eds. Amber, Resinite, and Fossil Resins. Washington, DC, 1995.

- Beck and Bouzek 1993

- Beck, C. W., and J. Bouzek, eds. Amber in Archaeology: Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Amber in Archaeology, Liblice, 1990. Prague, 1993.

- Beck and Shennan 1991

- Beck, C. W., and S. Shennan. Amber in Prehistoric Britain. Oxford, 1991.

- Bernstein 1996

- Ganzelewski, M., and R. Slotta, eds. Bernstein: Tränen der Götter. Exh. cat. Bochum, 1996.

- Grimaldi 1996

- Grimaldi, D. A. Amber: Window to the Past. New York, 1996.

- Langenheim 2003

- Langenheim, J. H. Plant Resins: Chemistry, Evolution, Ecology, and Ethnobotany. Portland, OR, 2003.

- Magie d’ambra 2005

- Magie d’ambra: Amuleti e gioielli della Basilicata antica. Exh. cat. Potenza, 2005.

- Nicholson and Shaw 2000

- Nicholson, P. T., and I. Shaw, eds. Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology. New York, 2000.

- Poinar and Poinar 1999

- Poinar, G. O., Jr., and R. Poinar. The Amber Forest: A Reconstruction of a Vanished World. Princeton, 1999.

- Pontin and Celi 2000

- Pontin, C., and M. Celi, eds. Ambra: Scrigno del tempo. Exh. cat. Montebelluna (Treviso), 2000.

- Ross 1998

- Ross, A. Amber: The Natural Time Capsule. London, 1998.

- Weitshaft and Wichard 2002

- Weitshaft, W., and W. Wichard. Atlas of Plants and Animals in Baltic Amber. Munich, 2002.